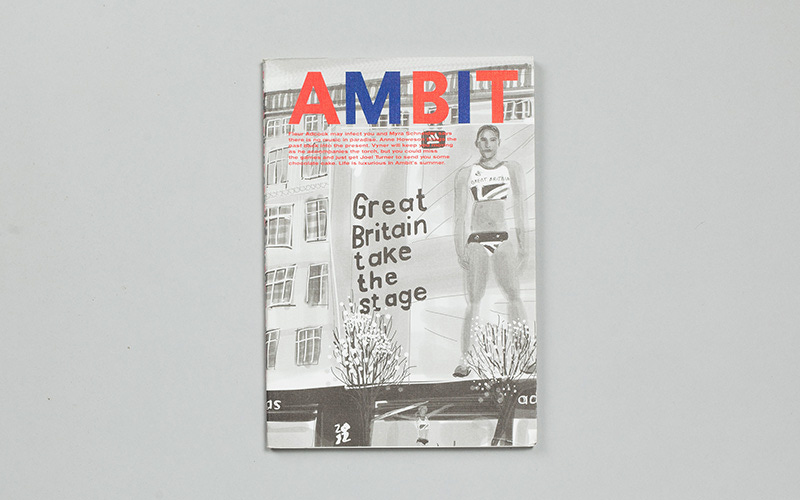

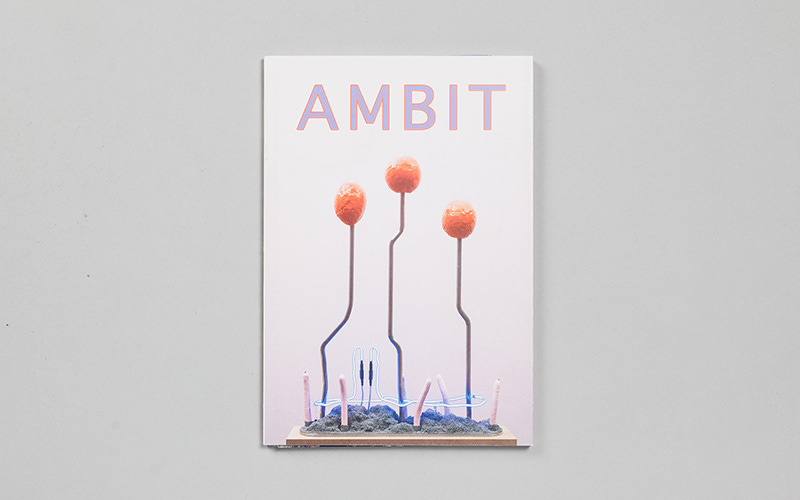

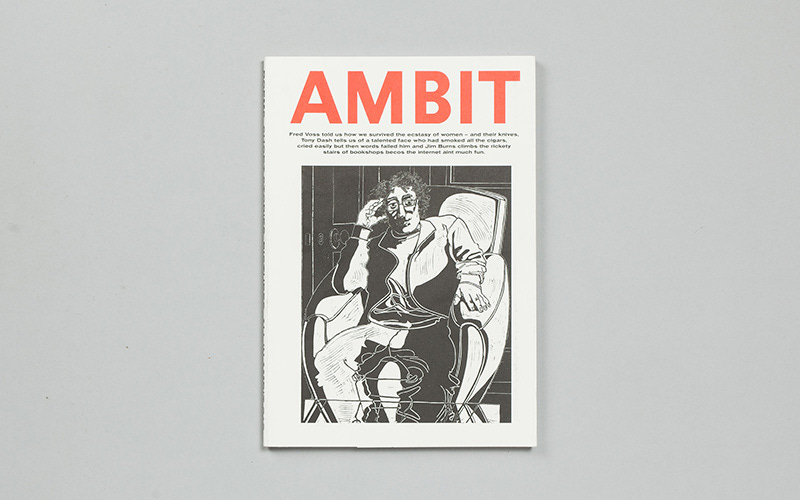

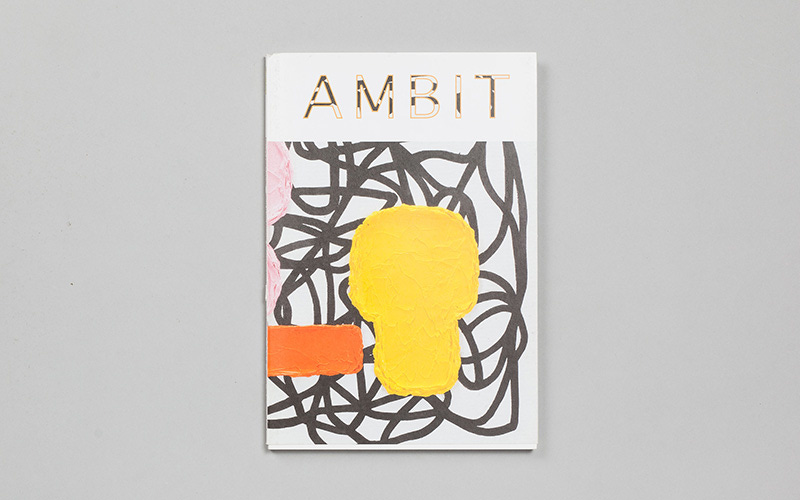

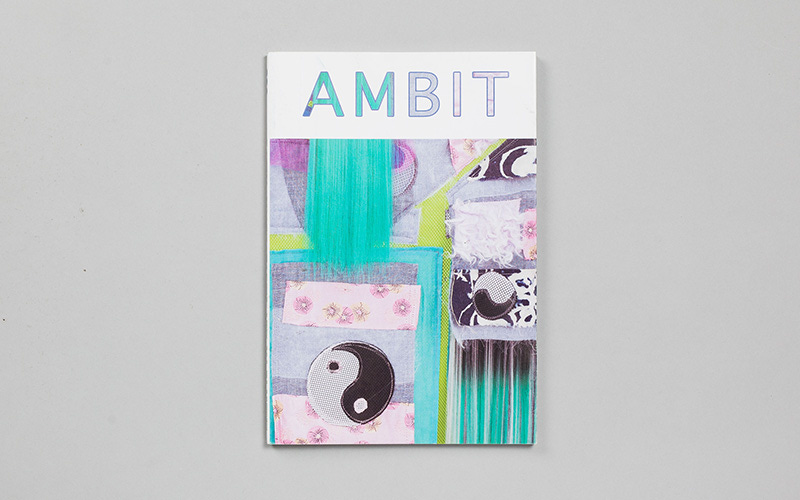

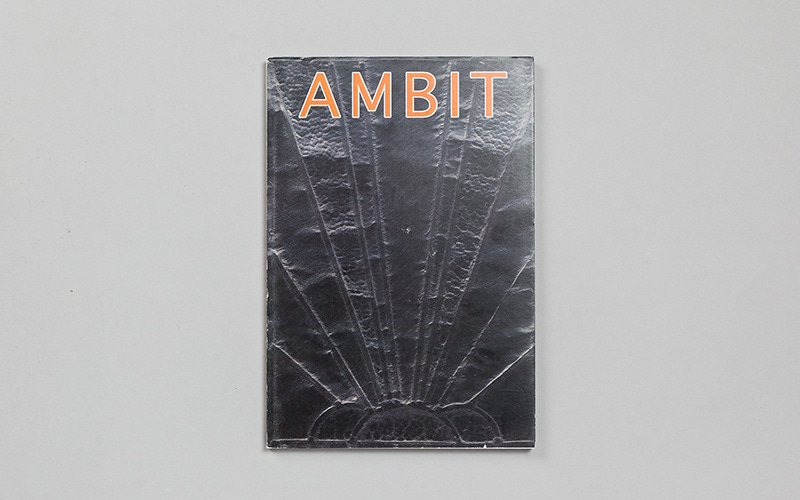

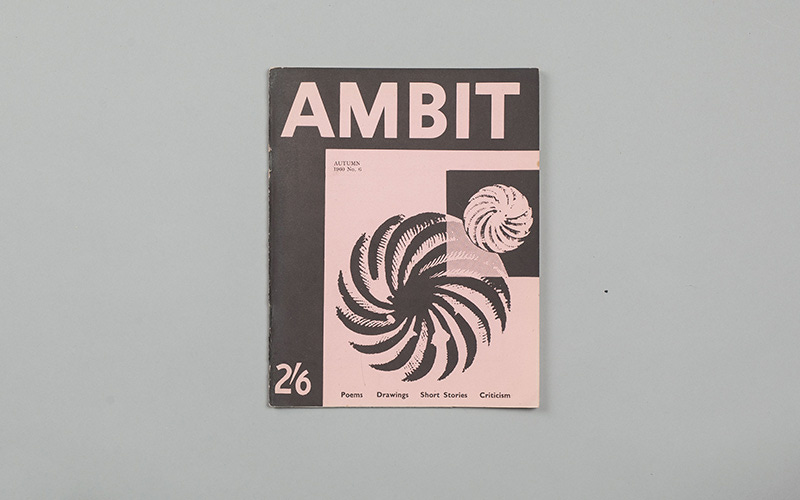

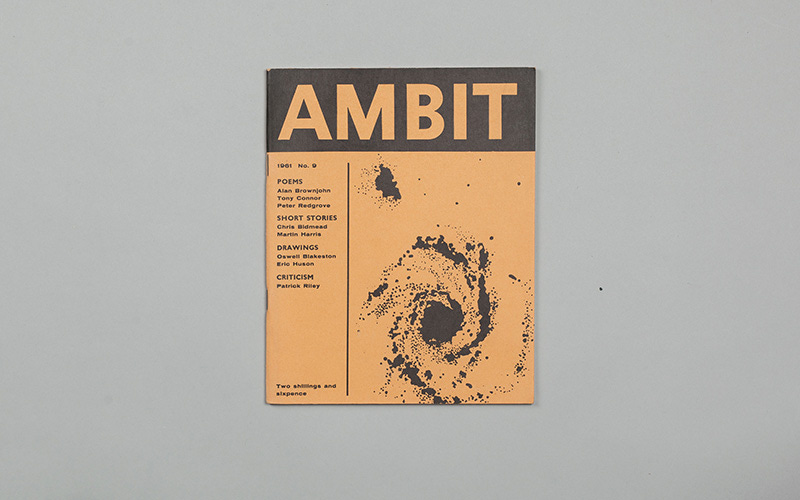

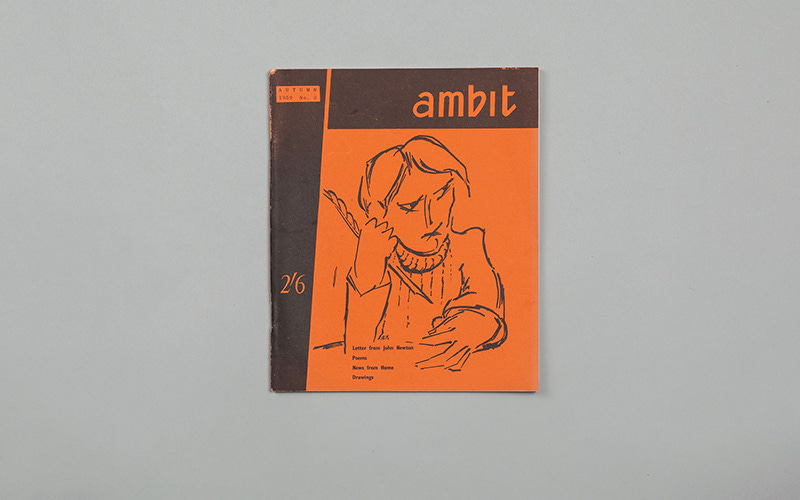

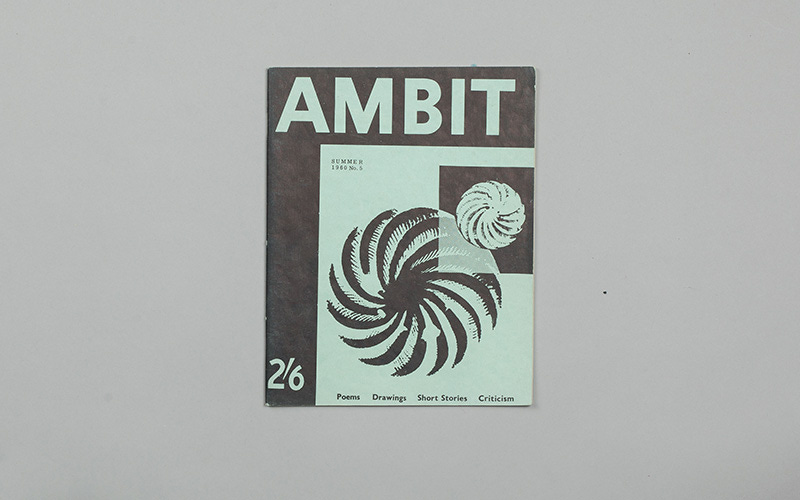

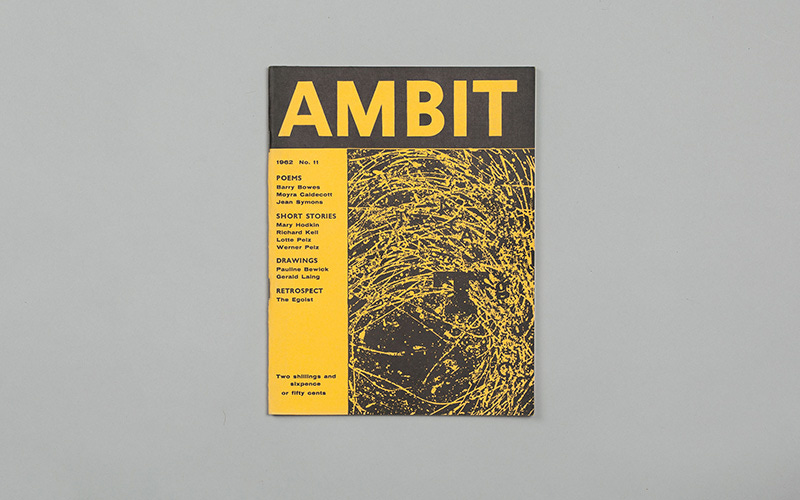

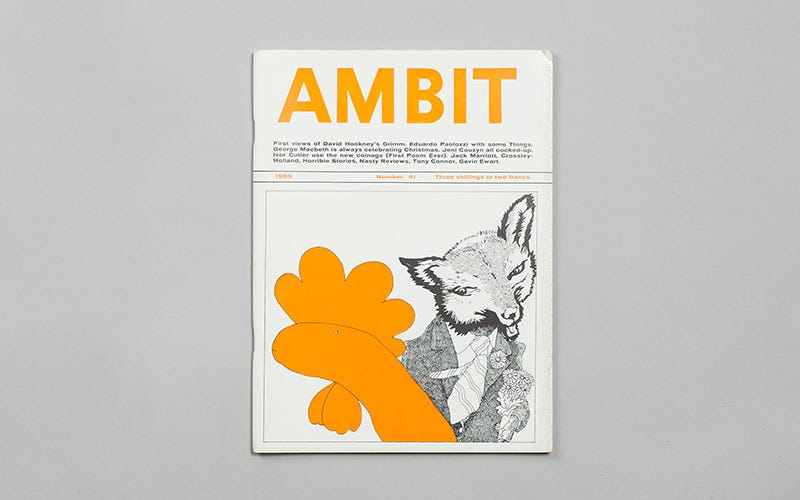

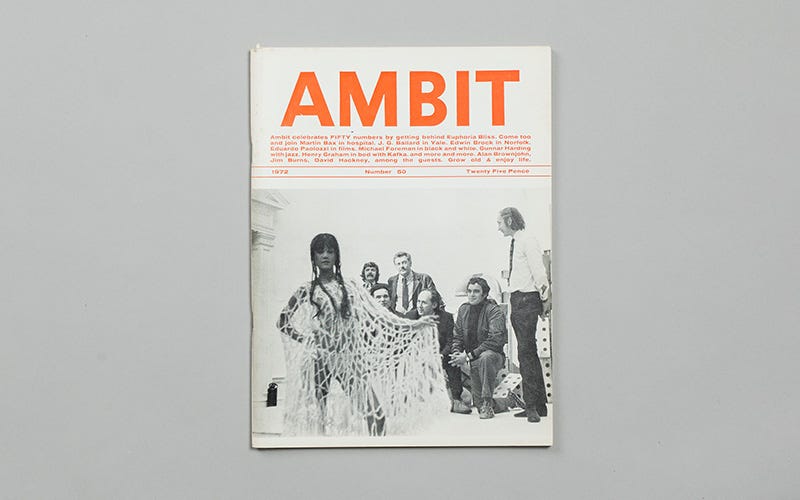

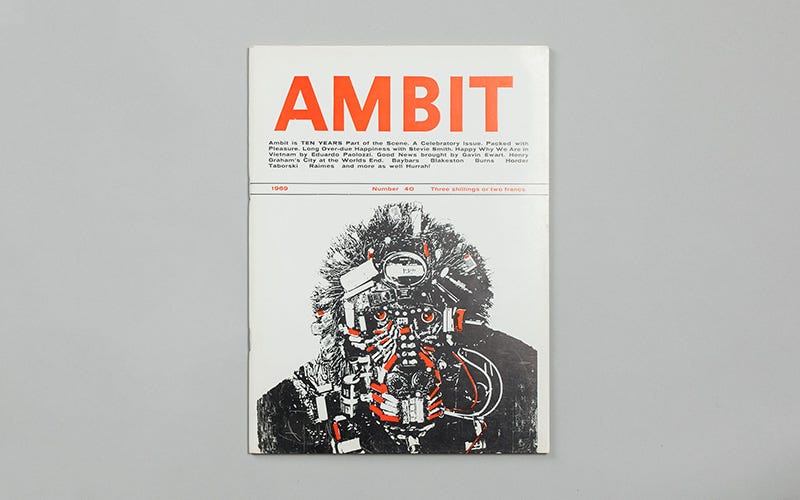

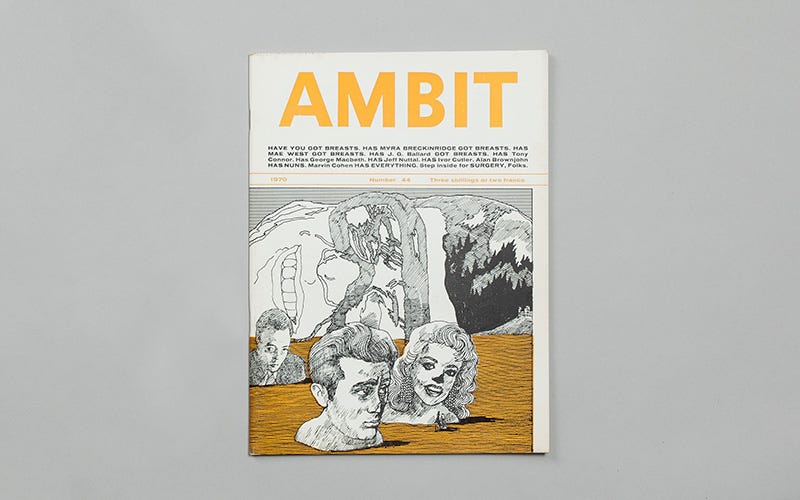

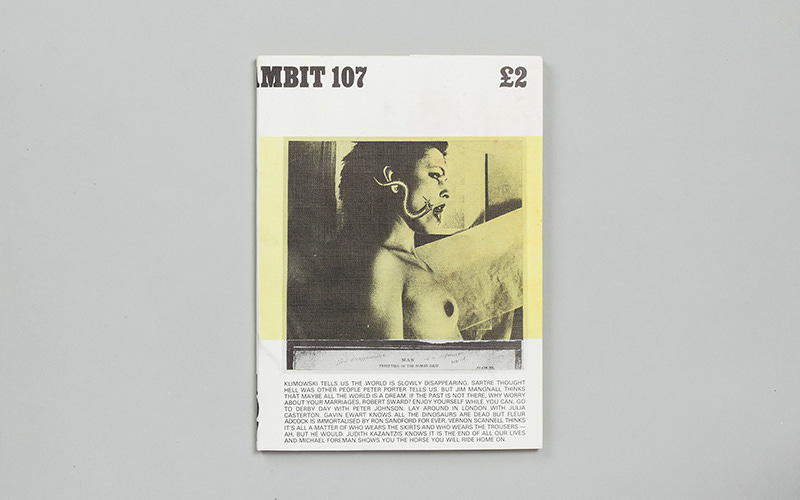

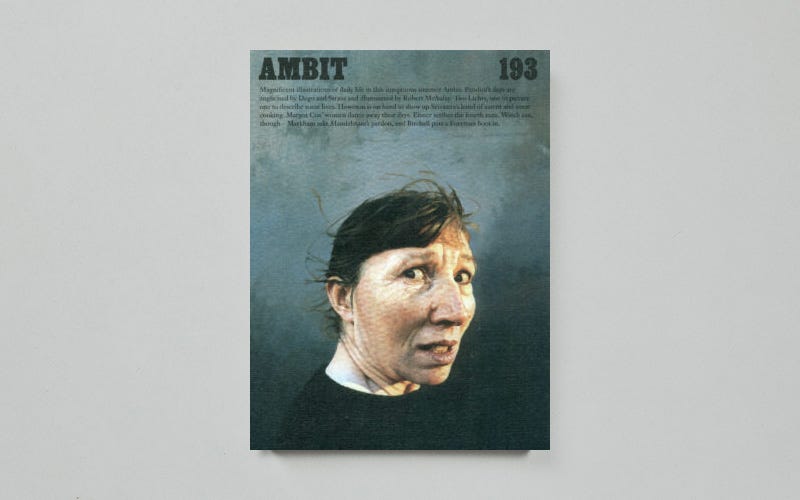

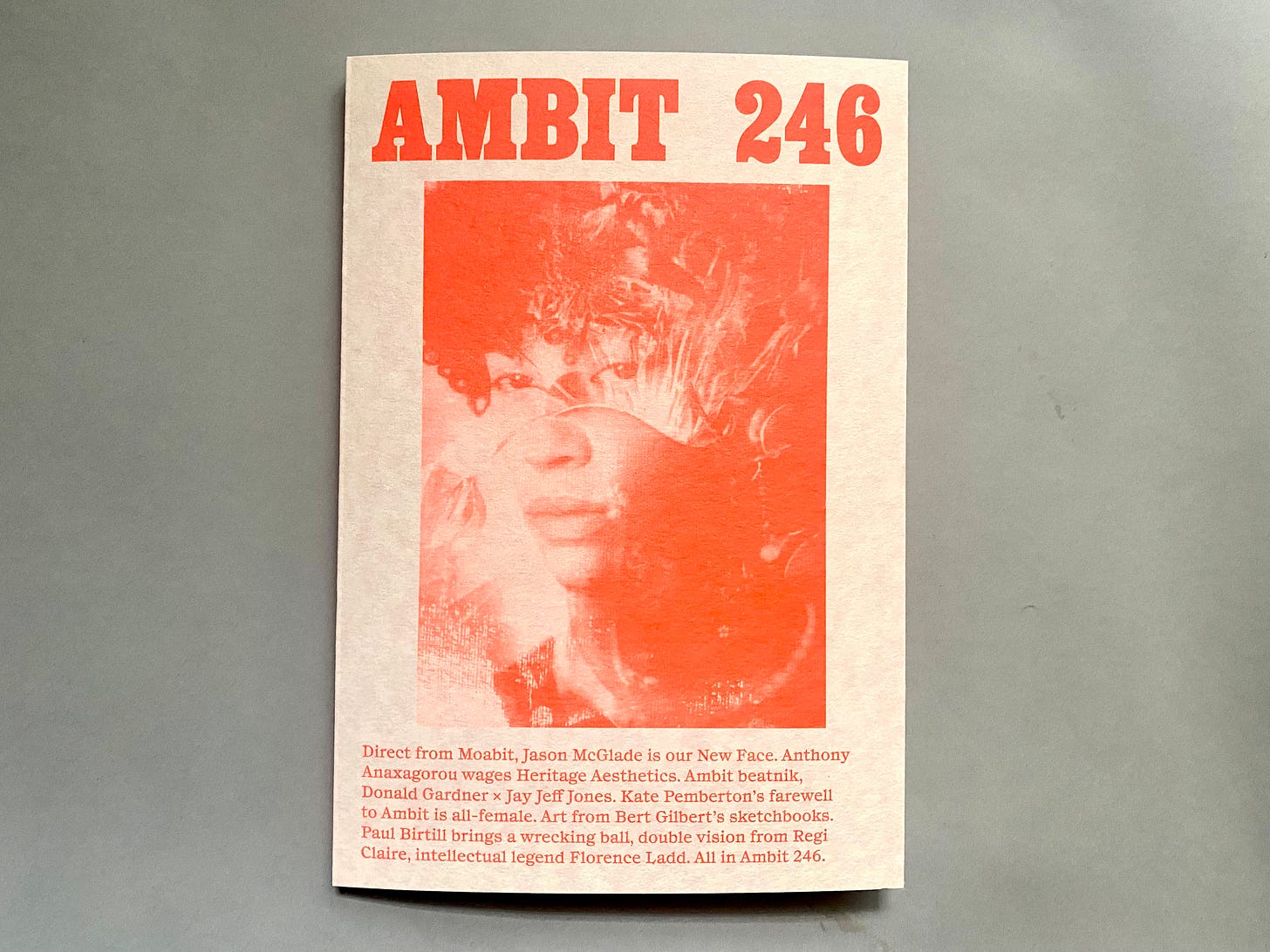

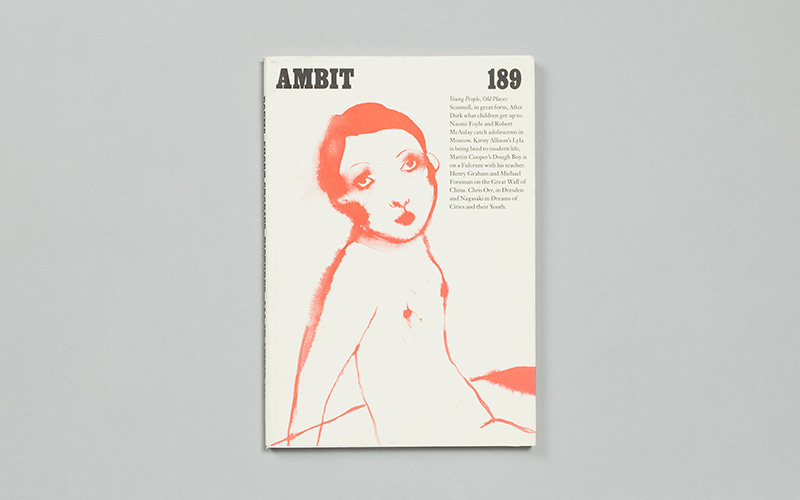

Dr Martin Bax, founder of the legendary British magazine Ambit, died peacefully in his sleep over the weekend of Spring’s equinox. It’s poetic he leaves in the season of hope and renewal, as that’s what he did for thousands of poets, writers and artists after establishing the magazine in 1959 from paper scraps of bins at a young Lavenham Press in Soho, who were publishing his papers as a radical and preeminent consultant paediatrician. Ambit ran quarterly until last year, maintaining our relationship with Lavenham Press until the end. I was proud to present our litho printed issues rather than the cheaper alternative of digital. Martin got to be pretty ancient, clocking up a grand total of ninety years on this beautifully contrary planet, born between the major wars of the twentieth century, in the August of 1933. He was also pretty ancient when I first met him in 2007 (above the Nellie Dean on Dean Street in Soho where I did my first (appalling) public reading for his 189th issue of Ambit). He appeared like a Roald Dahl kind of Father Christmas, larger than the many elves who joined his stable, lit by the many famous names he enabled. He came from that old fashioned world of collaboration, when trust was built on friendship, and mentorship came from the desire for a better world rather than a smarmy LinkedIn post.

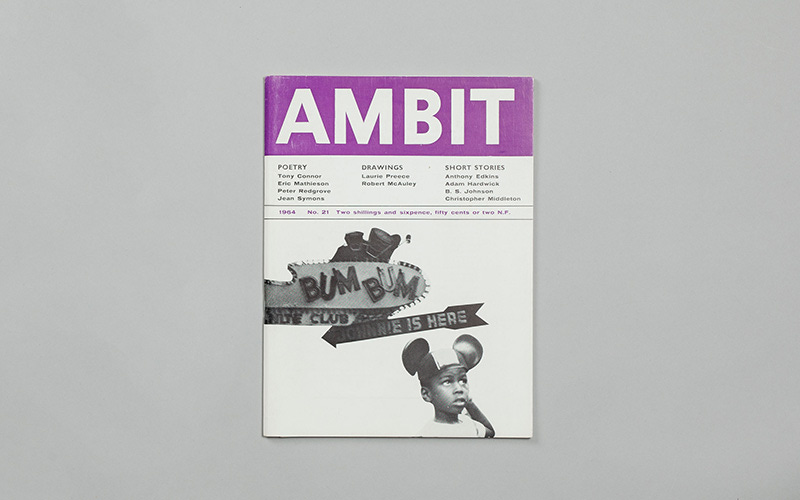

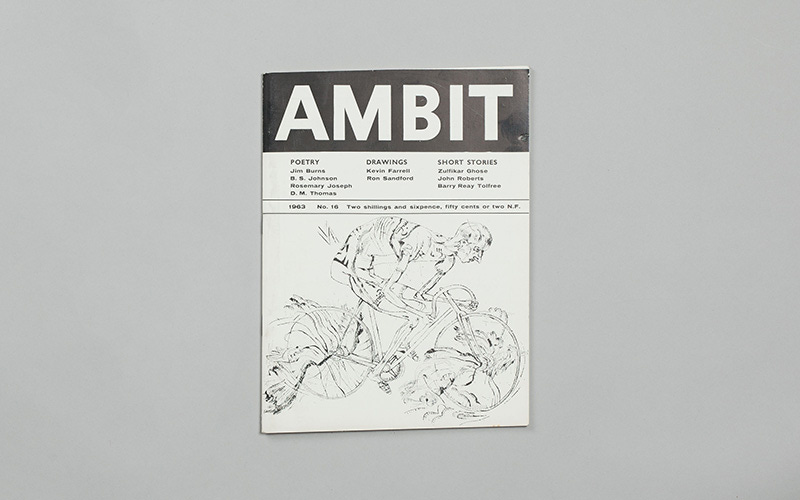

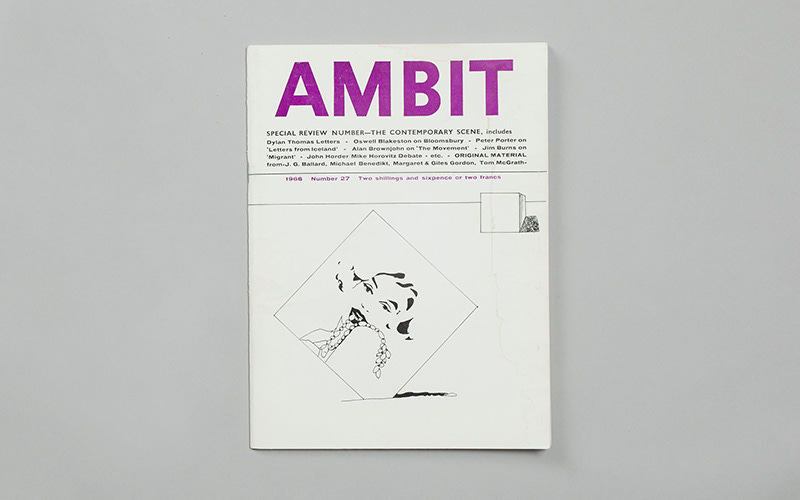

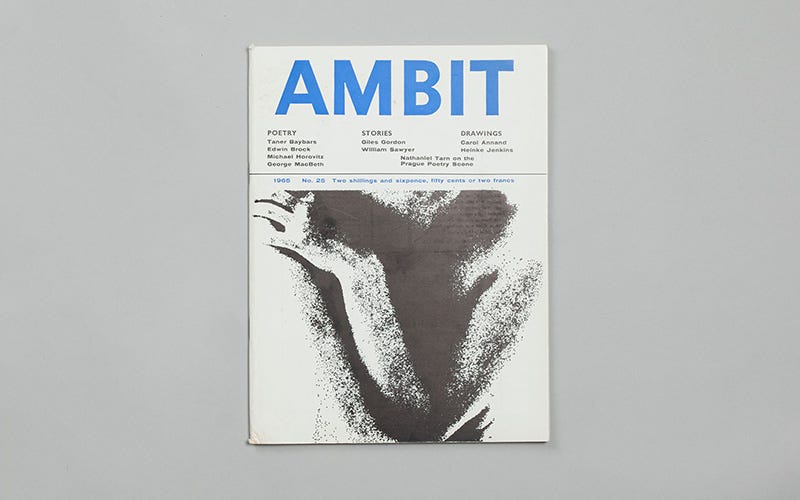

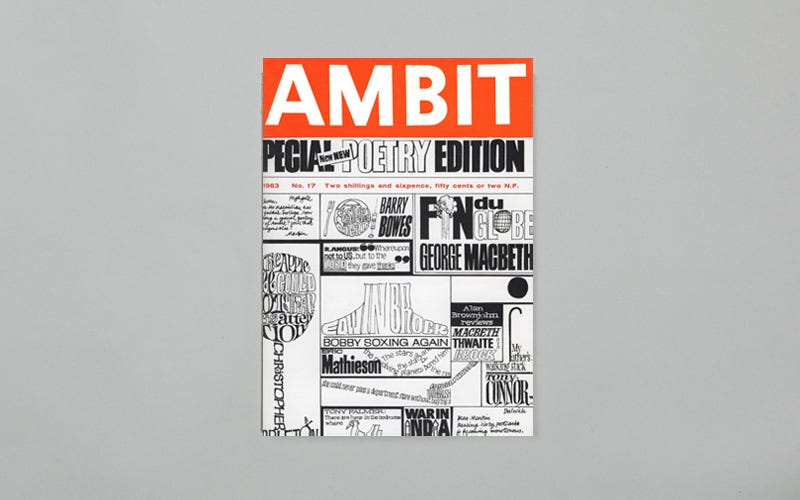

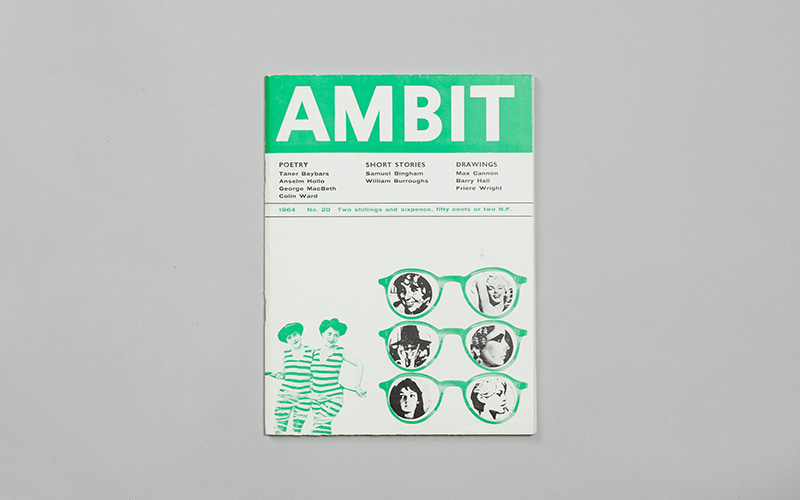

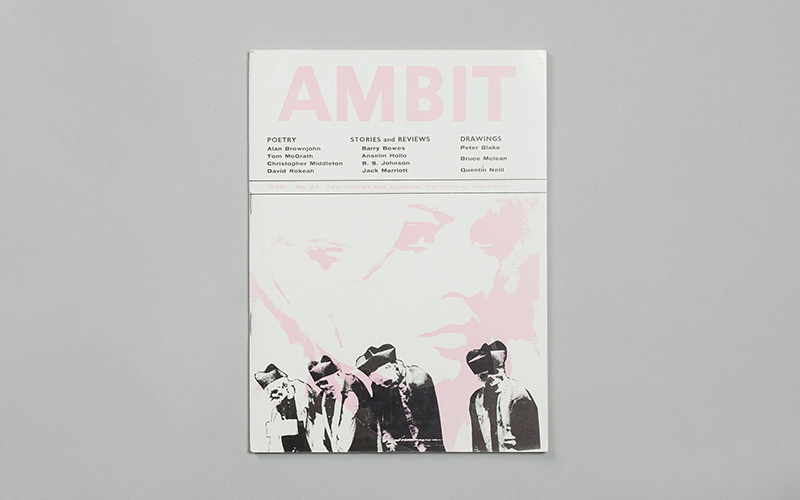

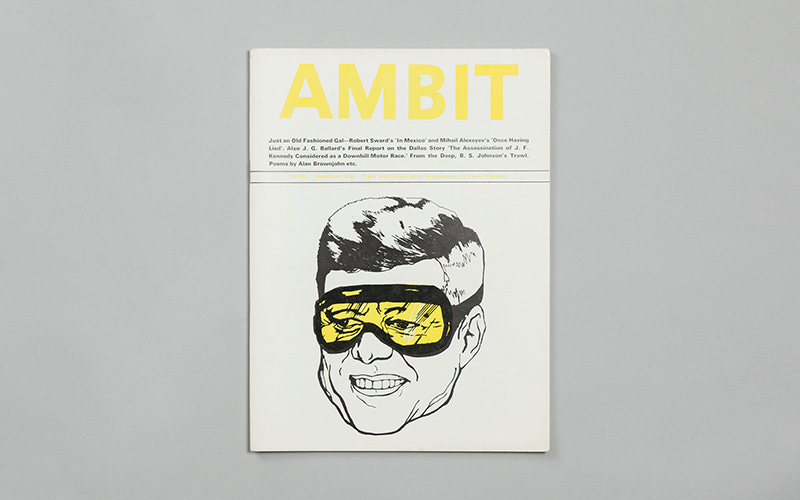

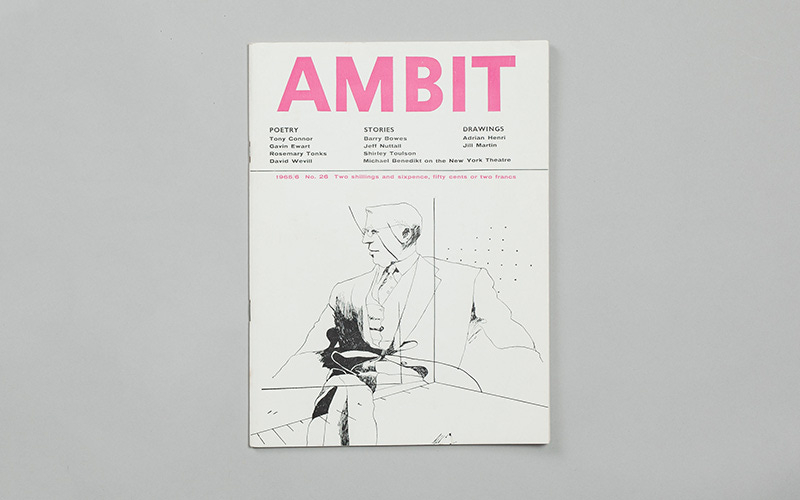

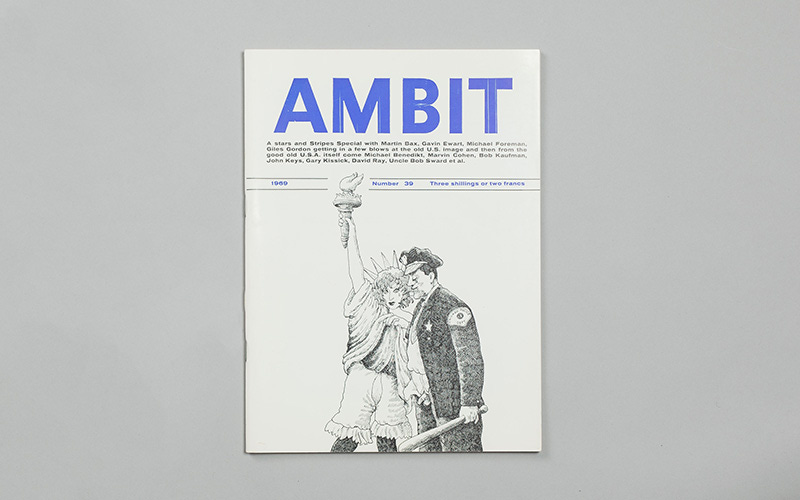

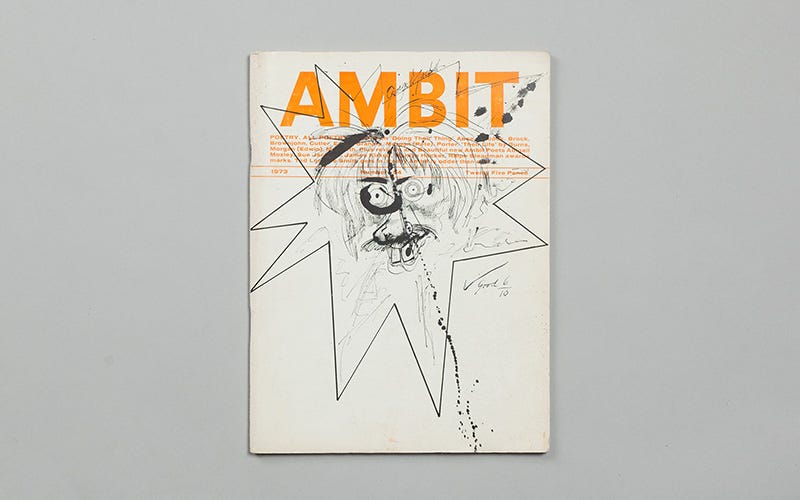

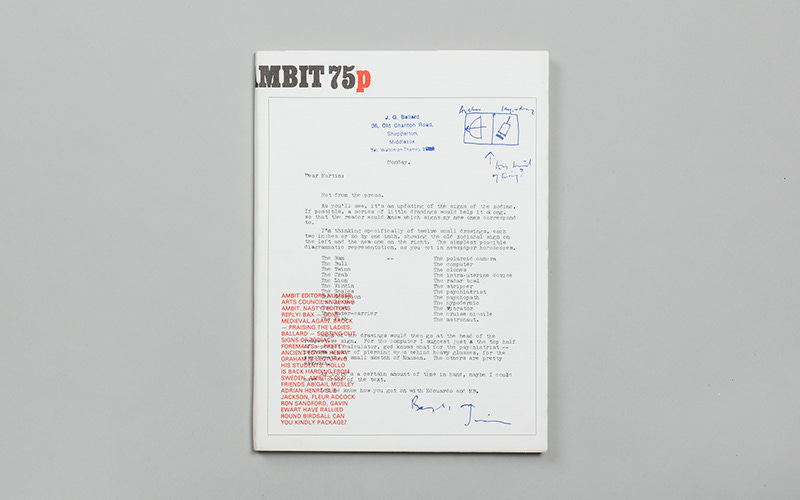

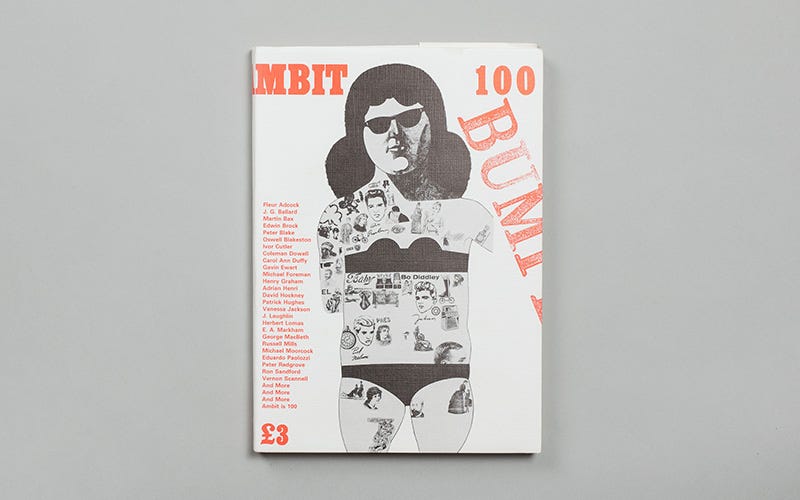

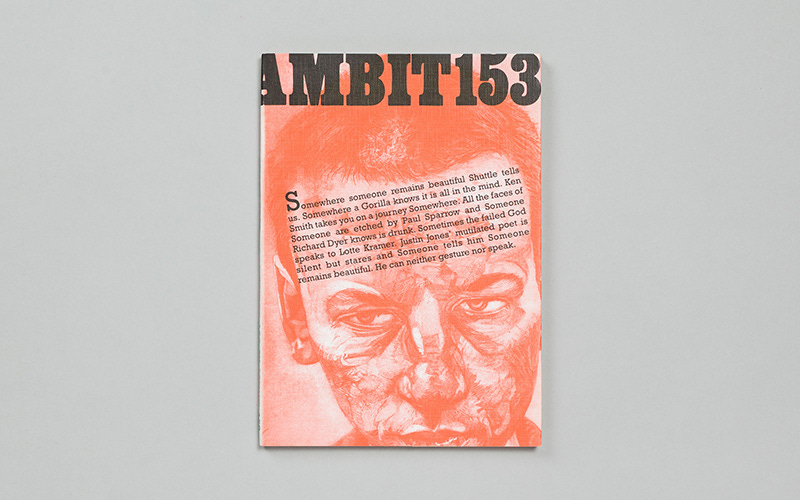

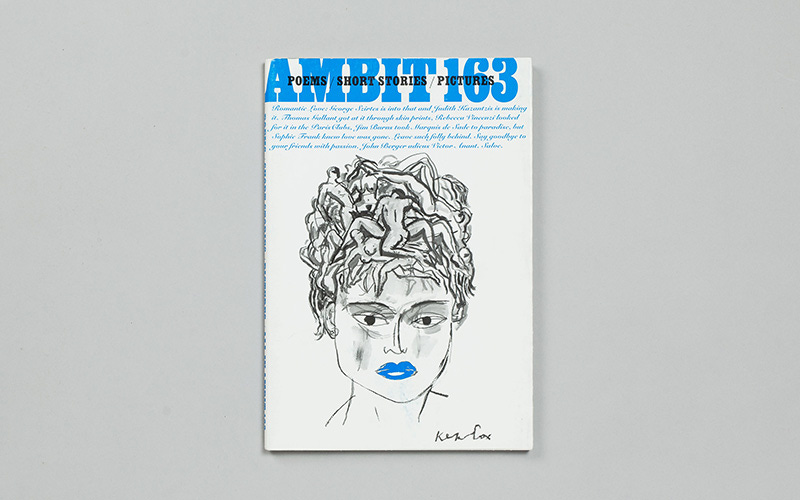

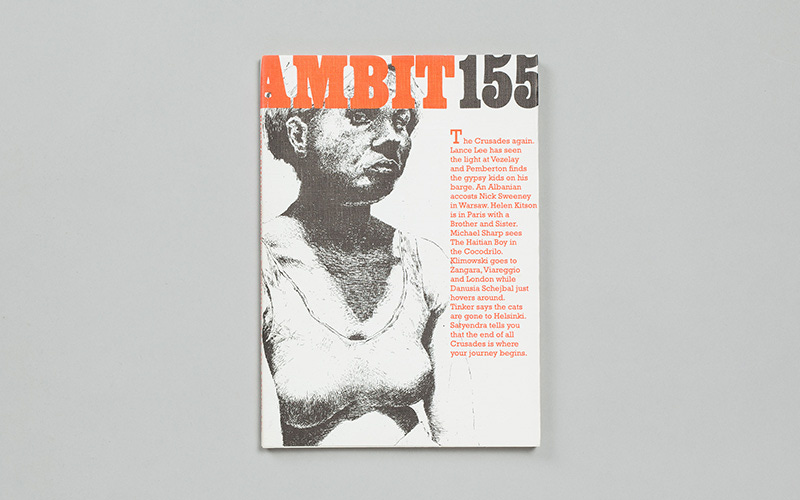

Martin Bax was one of those giraffe men, someone whose height could be said to attribute to his birds-eye talent in strategically facilitating a magazine I’d seen on posh people’s coffee tables since being a child. He was a visionary editor, an expert in the practice of publishing concise restrictions of experimentations. Tracking down JG Ballard, persuading him to first contribute in 1965, to the very rare Ambit 23, writing The Draining Lake; Jeff Nuttall was contributing to that issue too, alongside Beatles’ artist Peter Blake and Patrick Caulfield. In turn, Ballard introduced Eduardo Paolozzi to the group in 1967. Paolozzi was 43, relatively established*, already experimenting in cut-up iconography of media theory surrealism through the IG (Independent Group) based around the ICA. Paolozzi’s Krazy Kat archive was developing towards 20 000 images torn from print ephemera, collected in plastic bags (later bought by the V&A) to make collages from. Long before Google Image Search, when paper and jazz events held the concepts of “discovery” rather than Spotify’s algorithm, the cut and paste nature of Paolozzi echoed with the rising interest of the Dada methods popularised by Burroughs, and later Bowie, but also of the hot metal necessities of printing imagery at the time (think of Man Ray’s early photographic and printing techniques). Ambit provided a space to experiment, play, collaborate and connect, with bilateral exchanges from working class artists like Ken Cox, whose induction to printing and design art school led him to meet people like Martin who introduced Cox to future patrons via the Chelsea Arts Club. These were days when advertising was not ingrained into British culture and consumerism was not the drive to everything, yet that culture could still be distinguished as a dystopian threat to generations who were familiar with the brutalities of war and conscription. Advertising, alongside America was something to fear and consider oneself stupid to become a victim to. The magazine largely ignored advertising throughout all the issues, unless used for comedic or surreal pastiches, unless it was to bring attention to something serious by those establishments able to support Ambit’s efforts. Not to say there weren’t vague attempts at commercialisation at Ambit, people trying ‘development’ of the brand, with advertising assistants listed in the masthead and the consistent attitude of going against the establishment to create positive change from Ambit’s HQ, but it was never about the money.

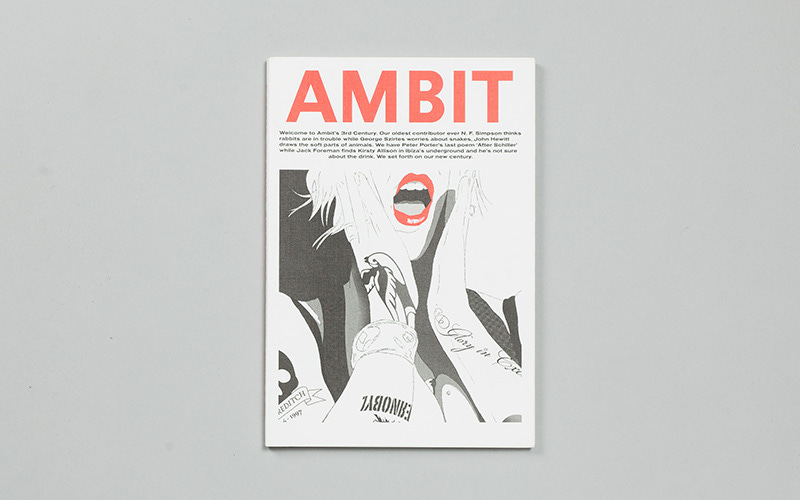

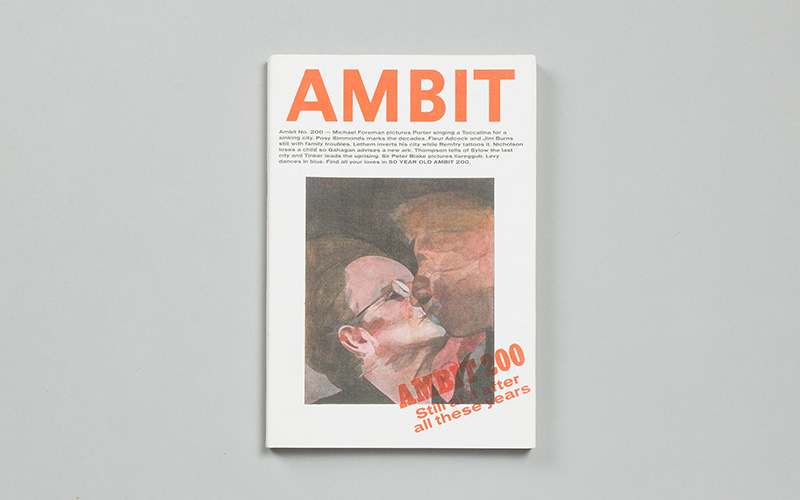

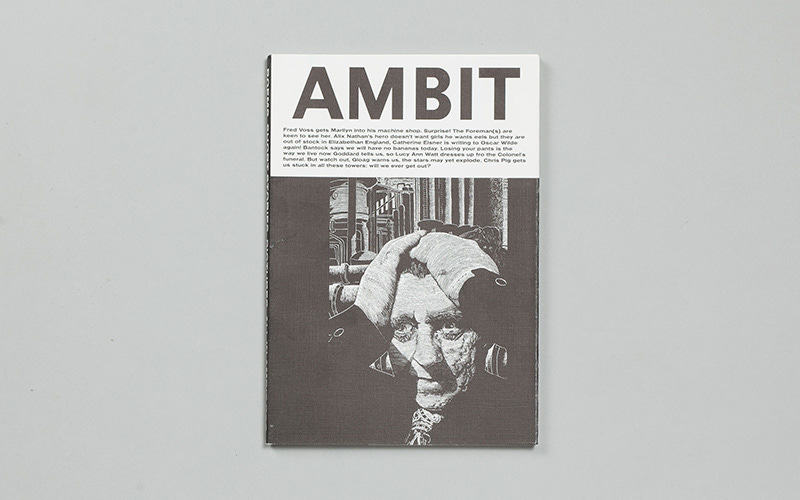

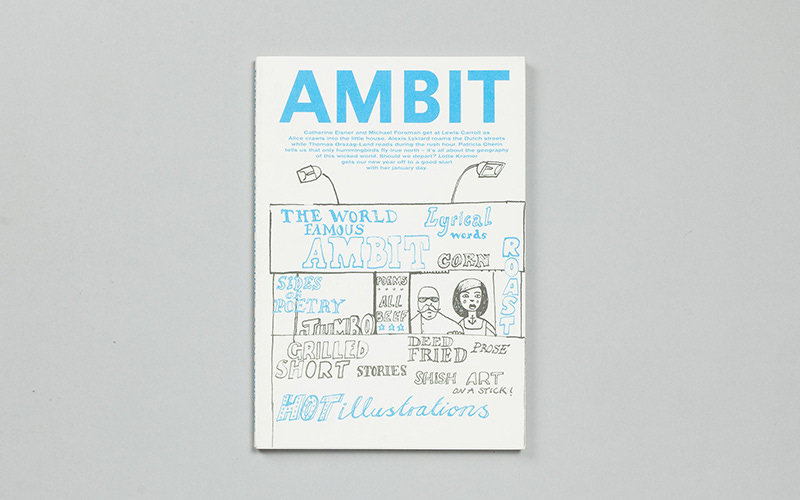

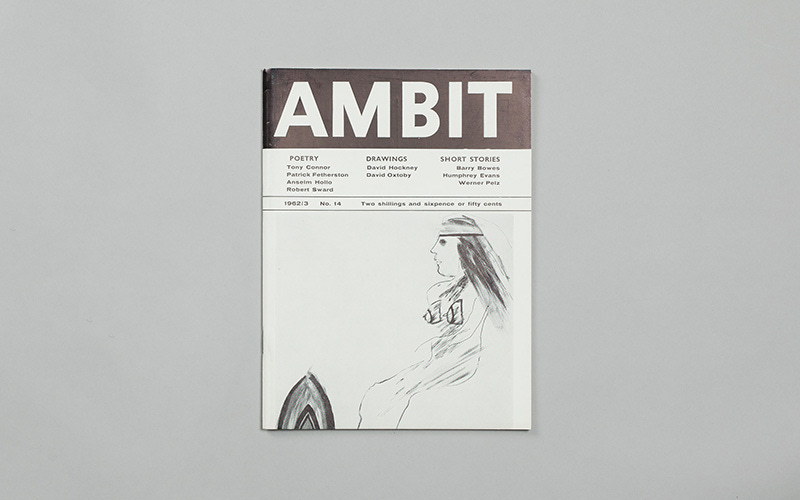

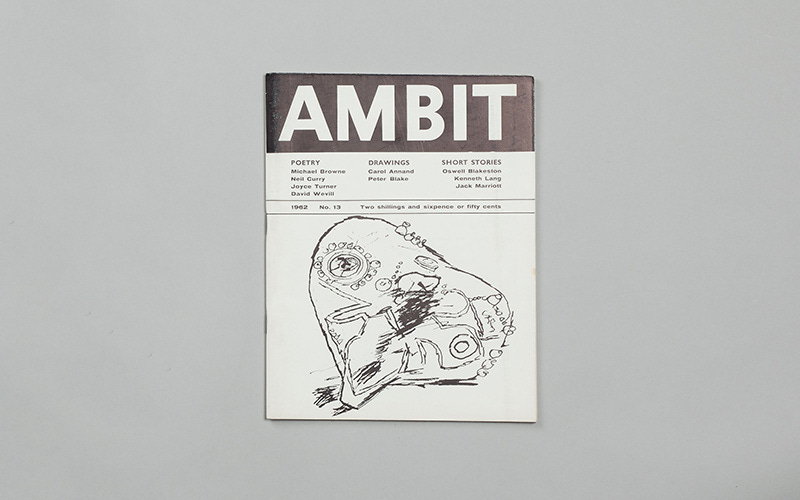

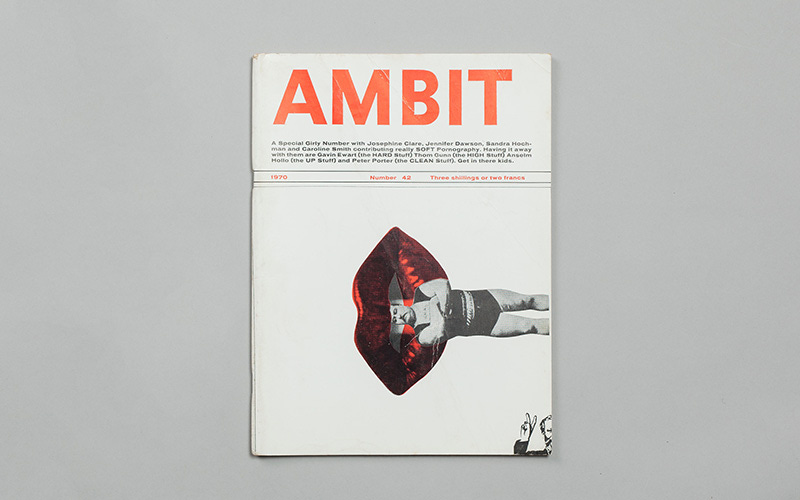

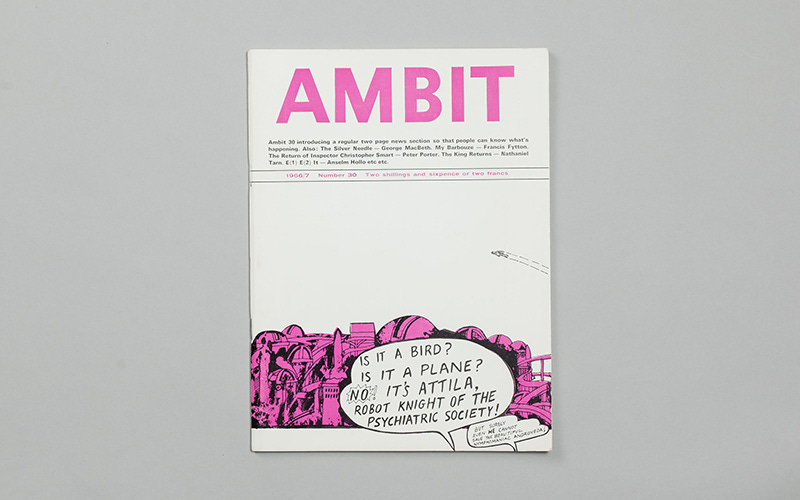

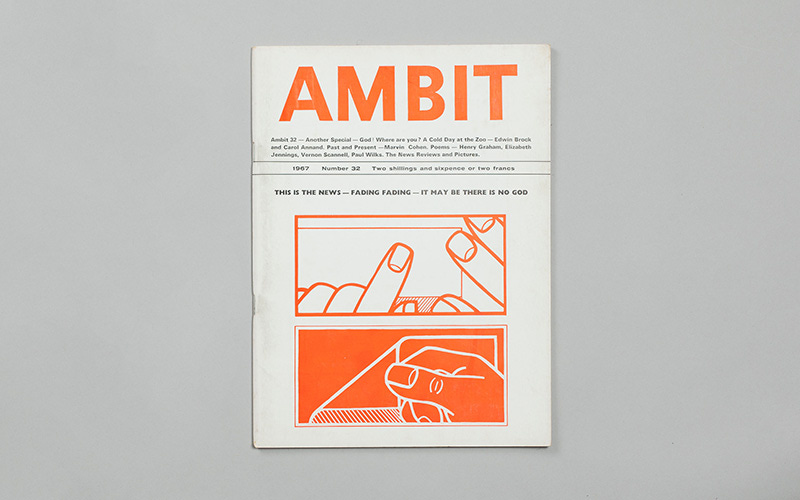

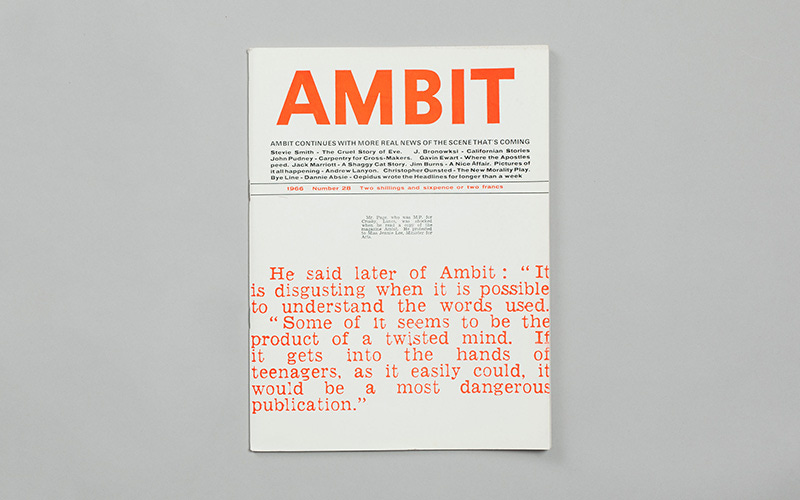

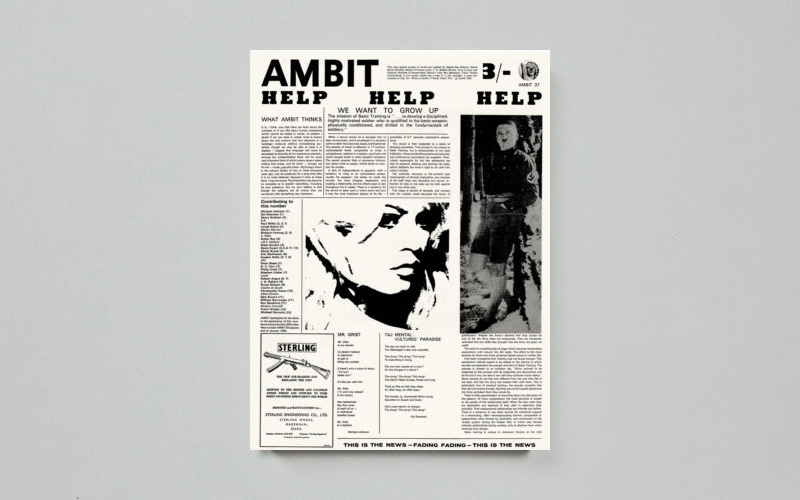

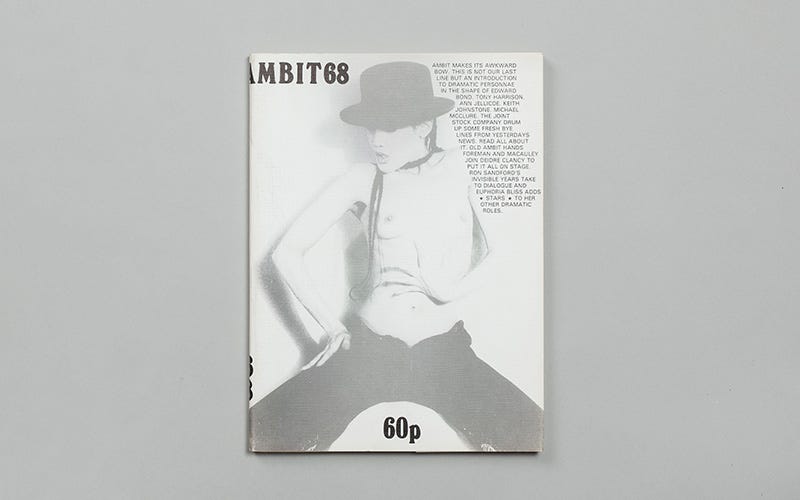

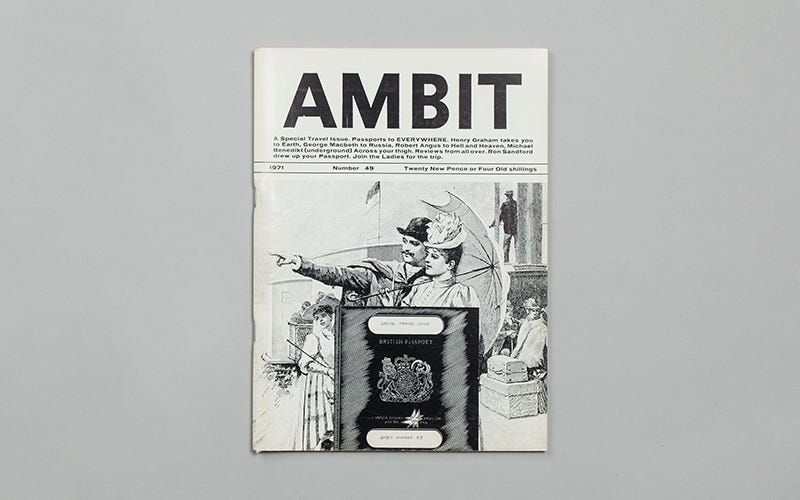

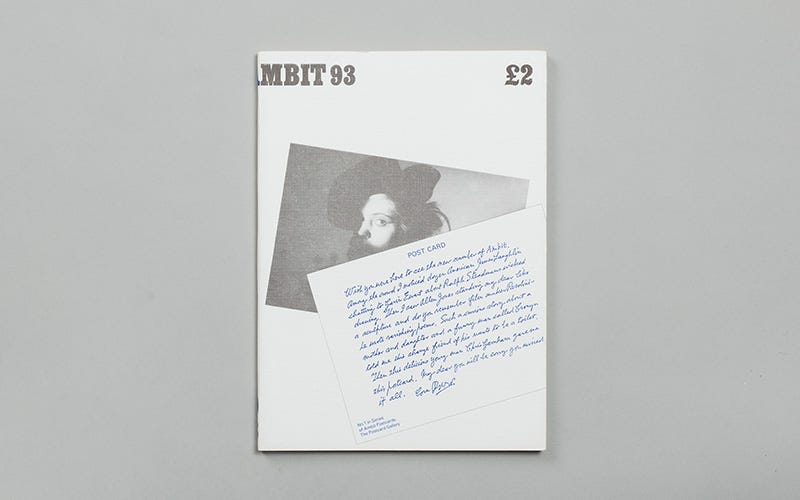

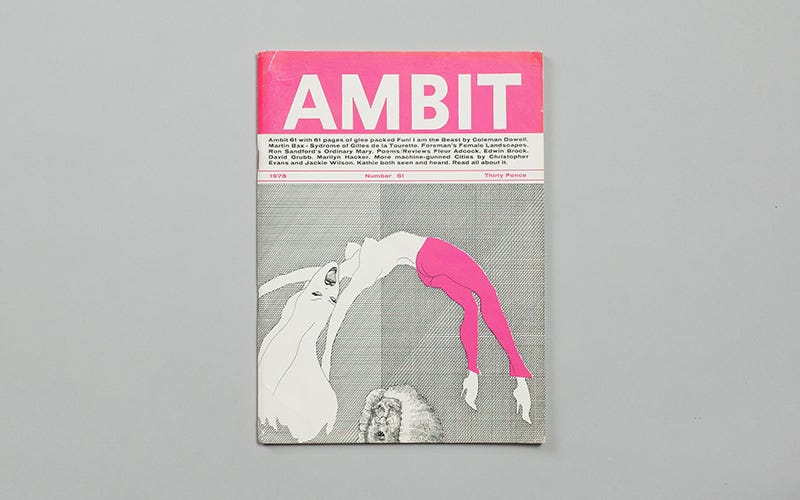

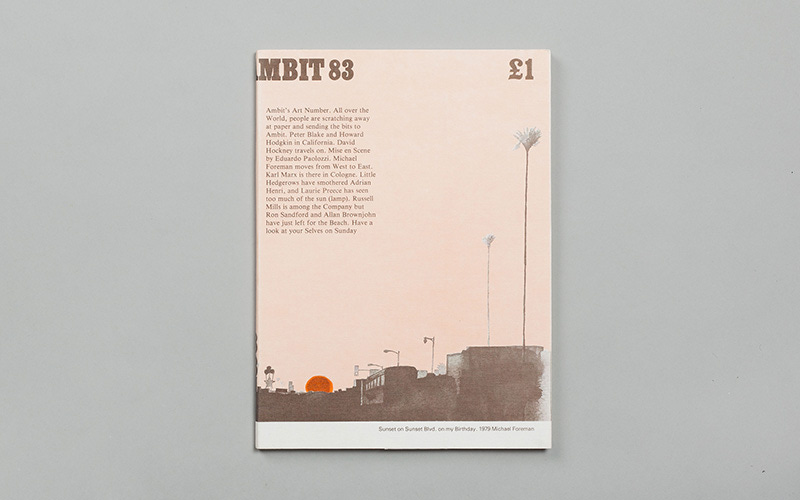

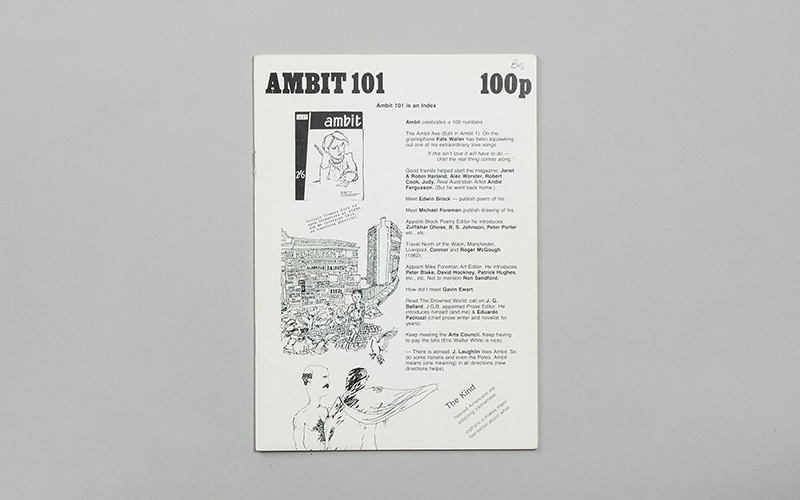

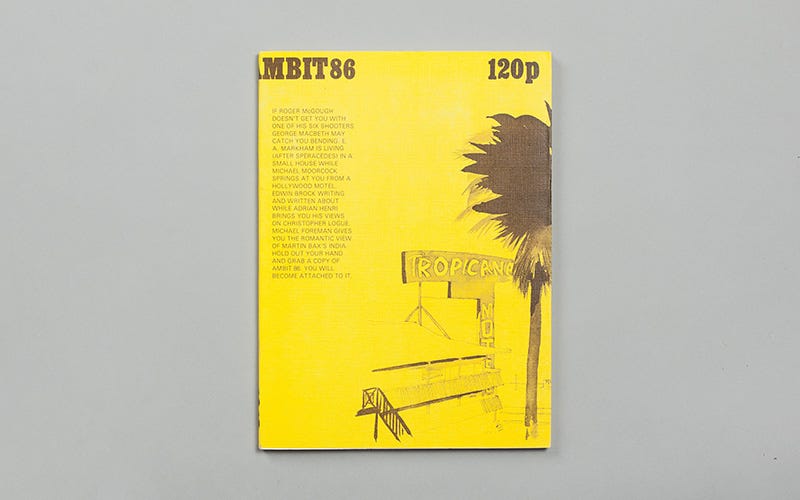

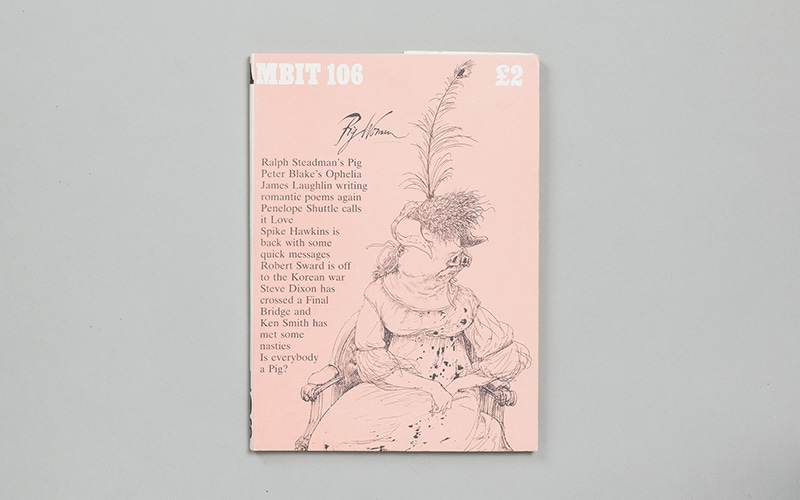

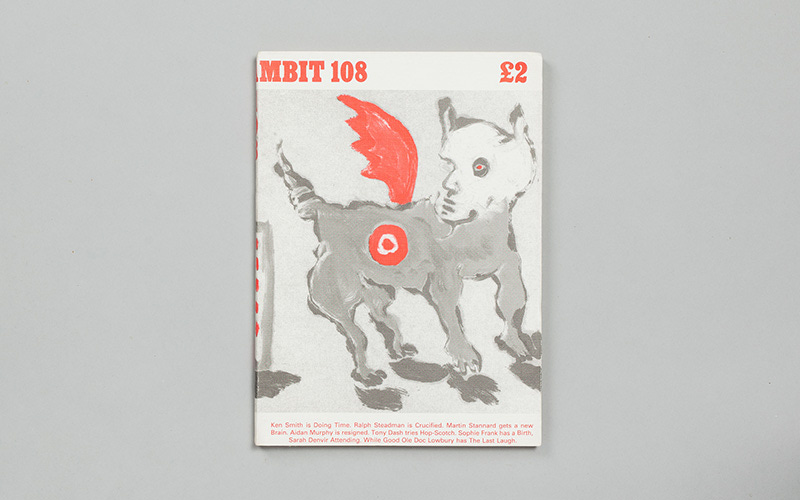

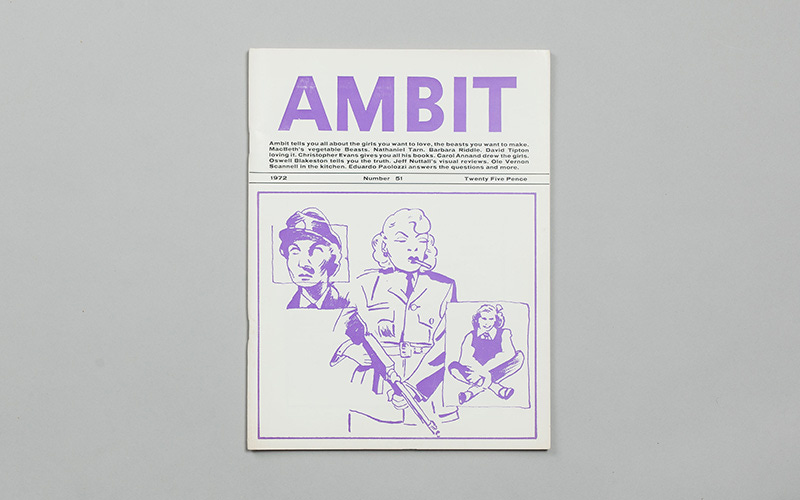

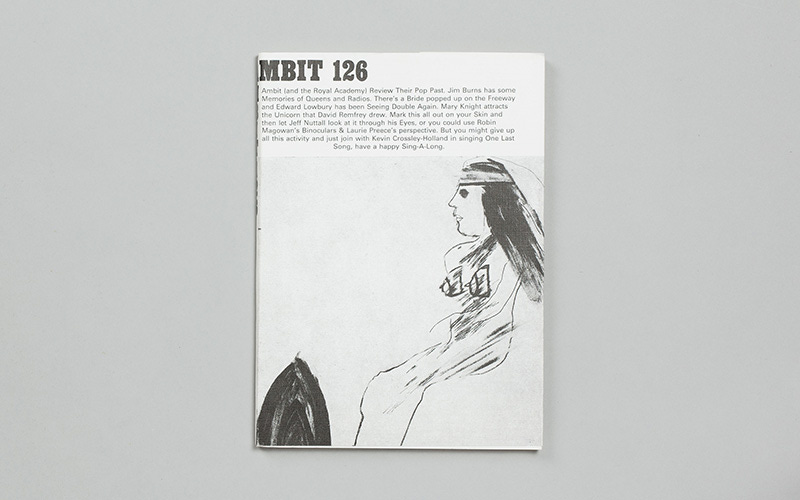

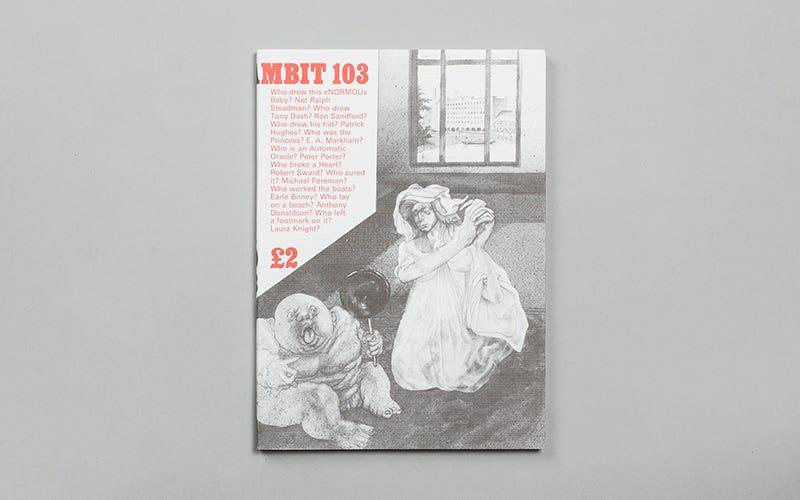

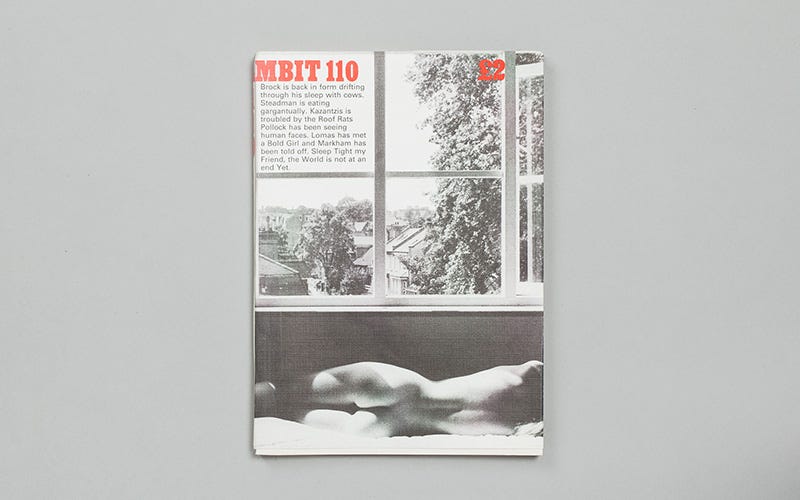

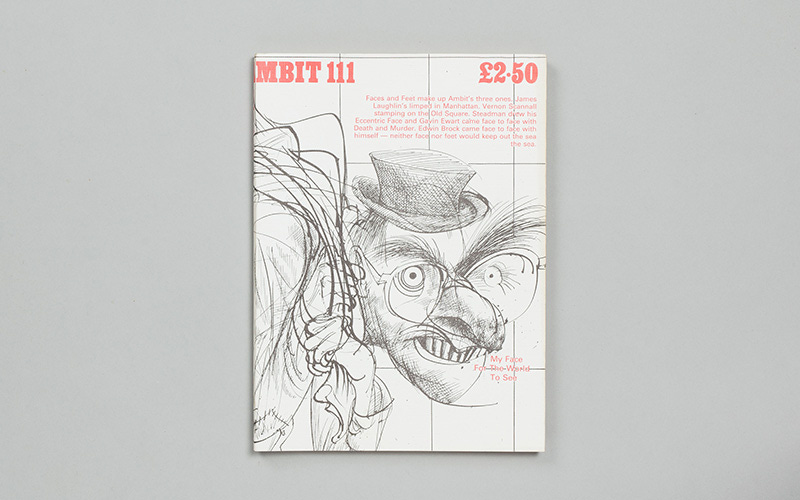

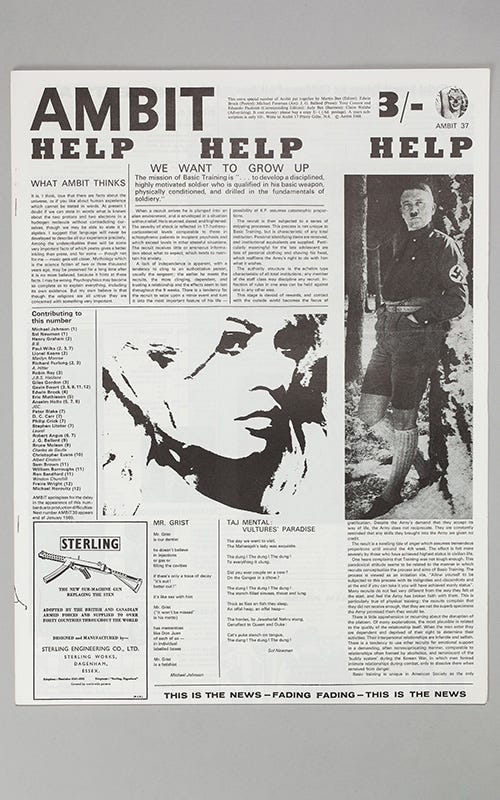

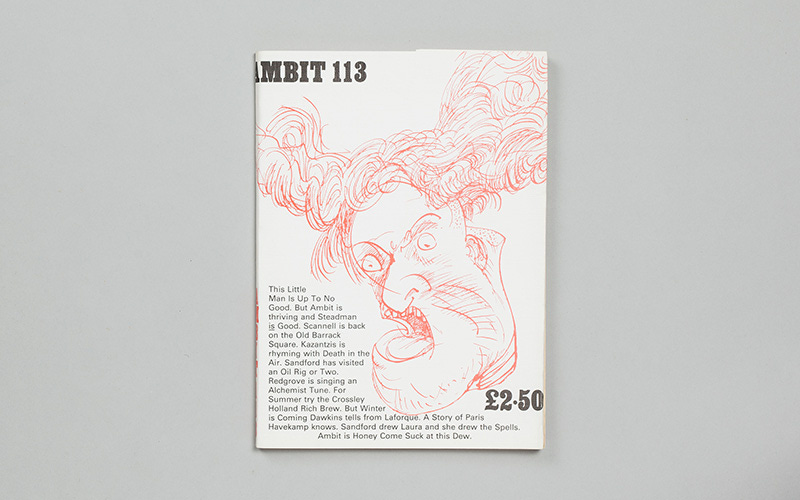

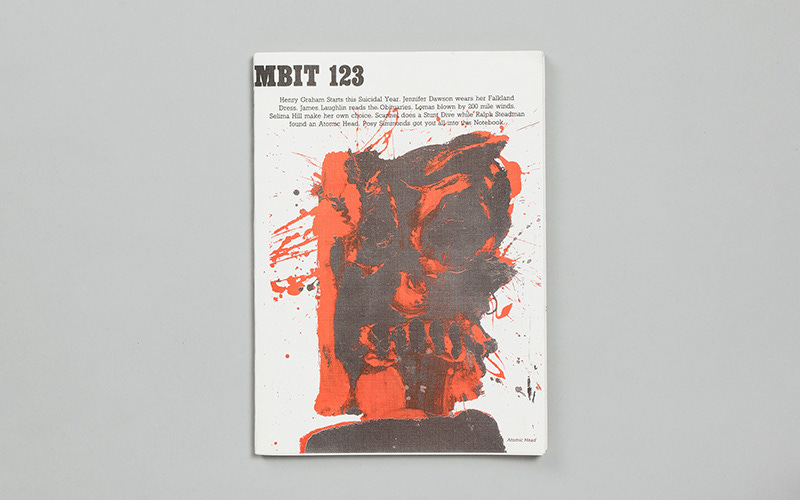

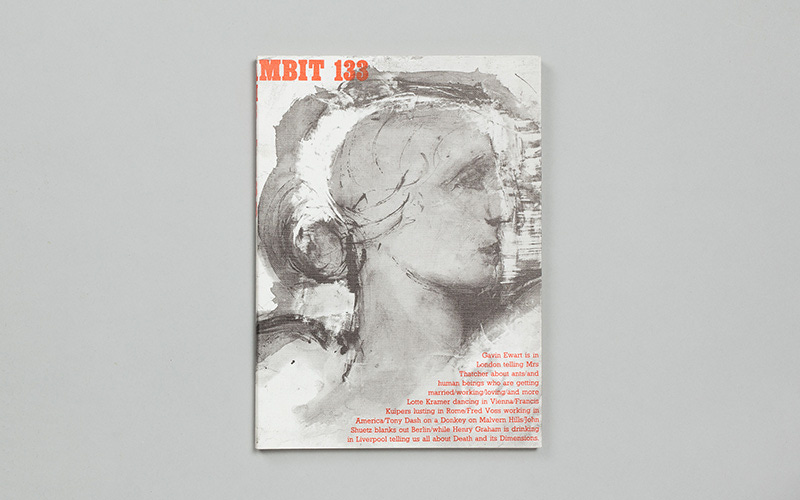

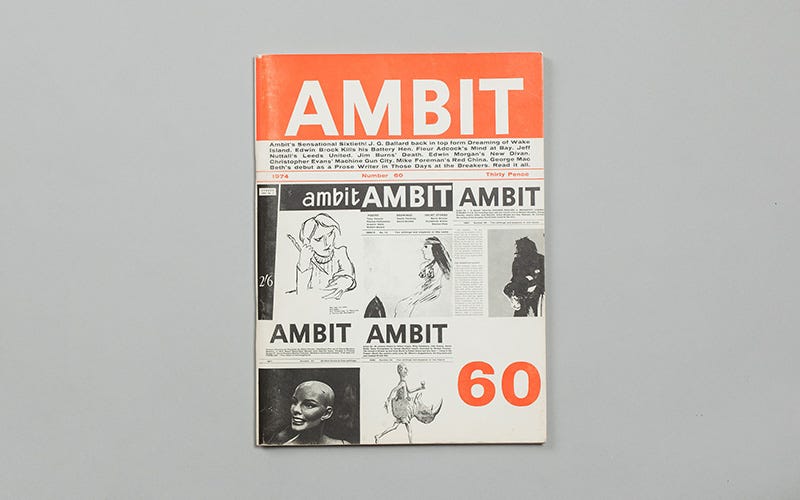

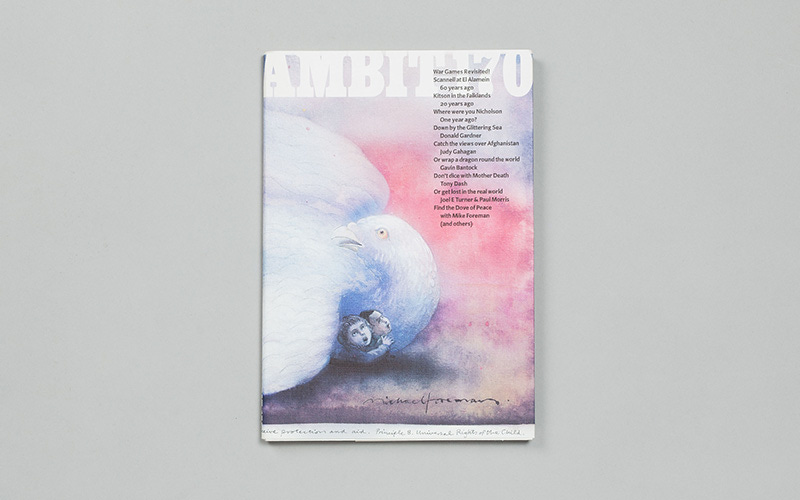

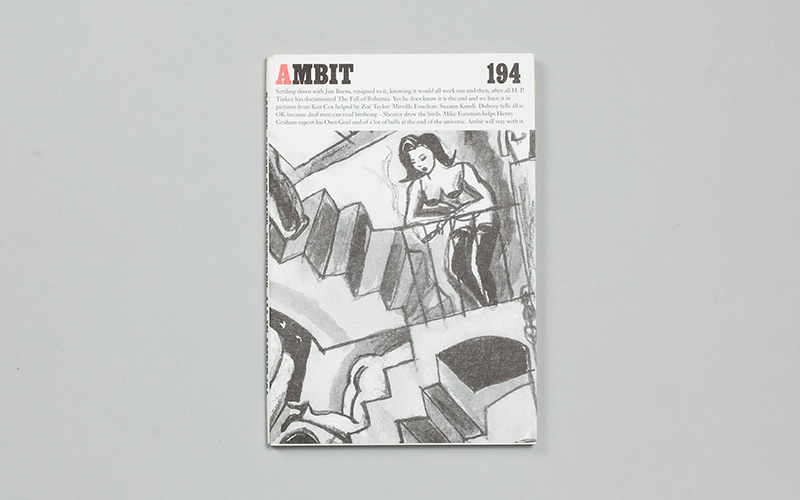

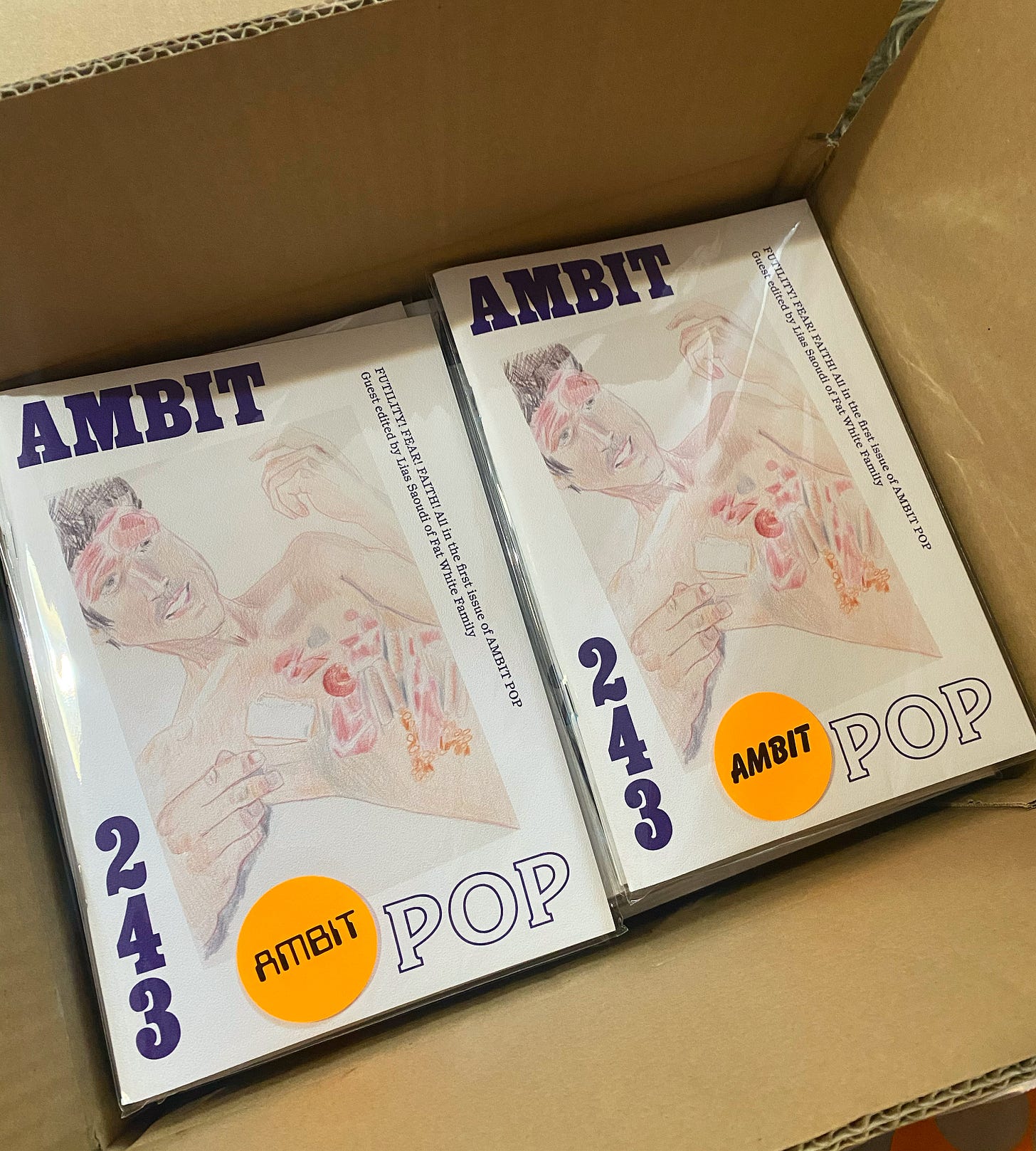

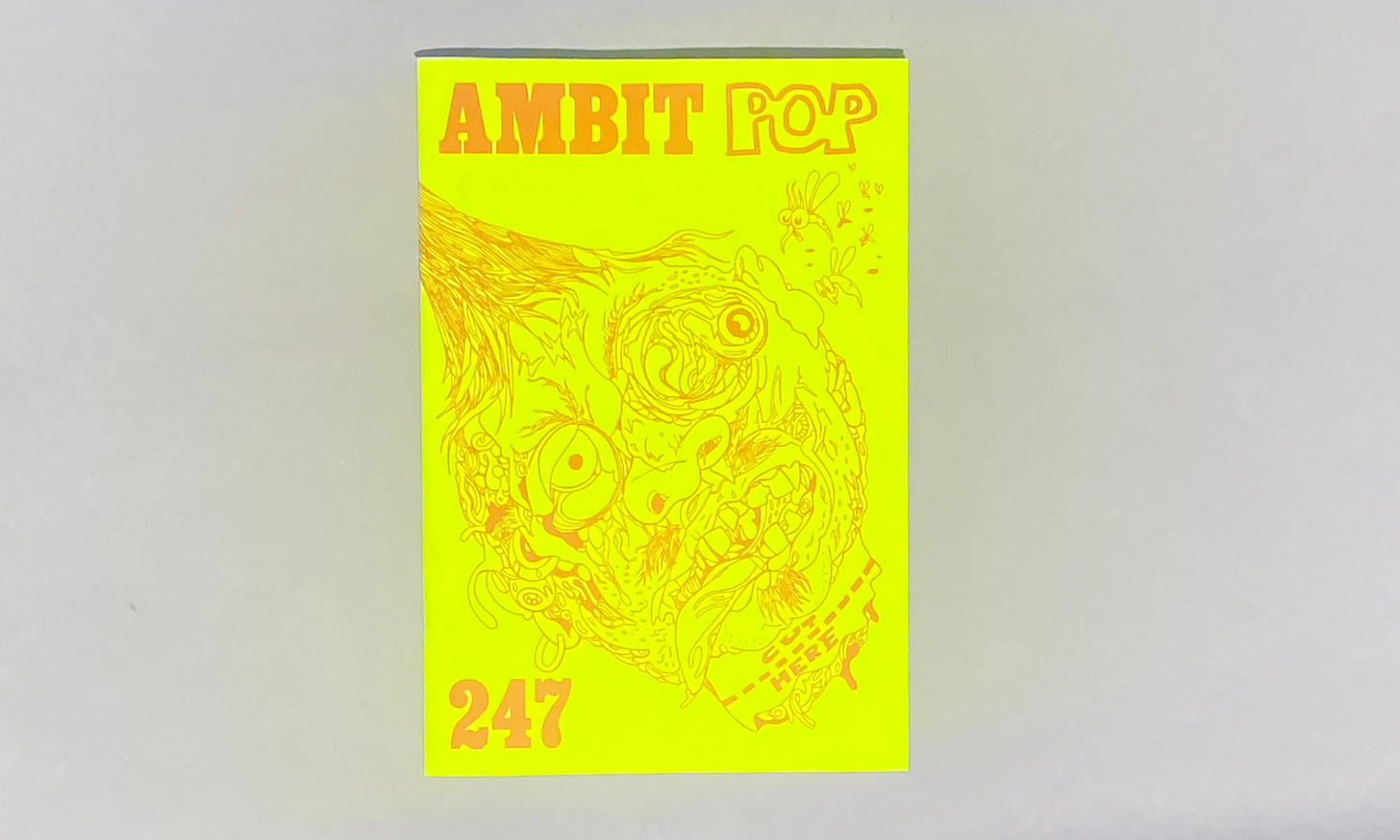

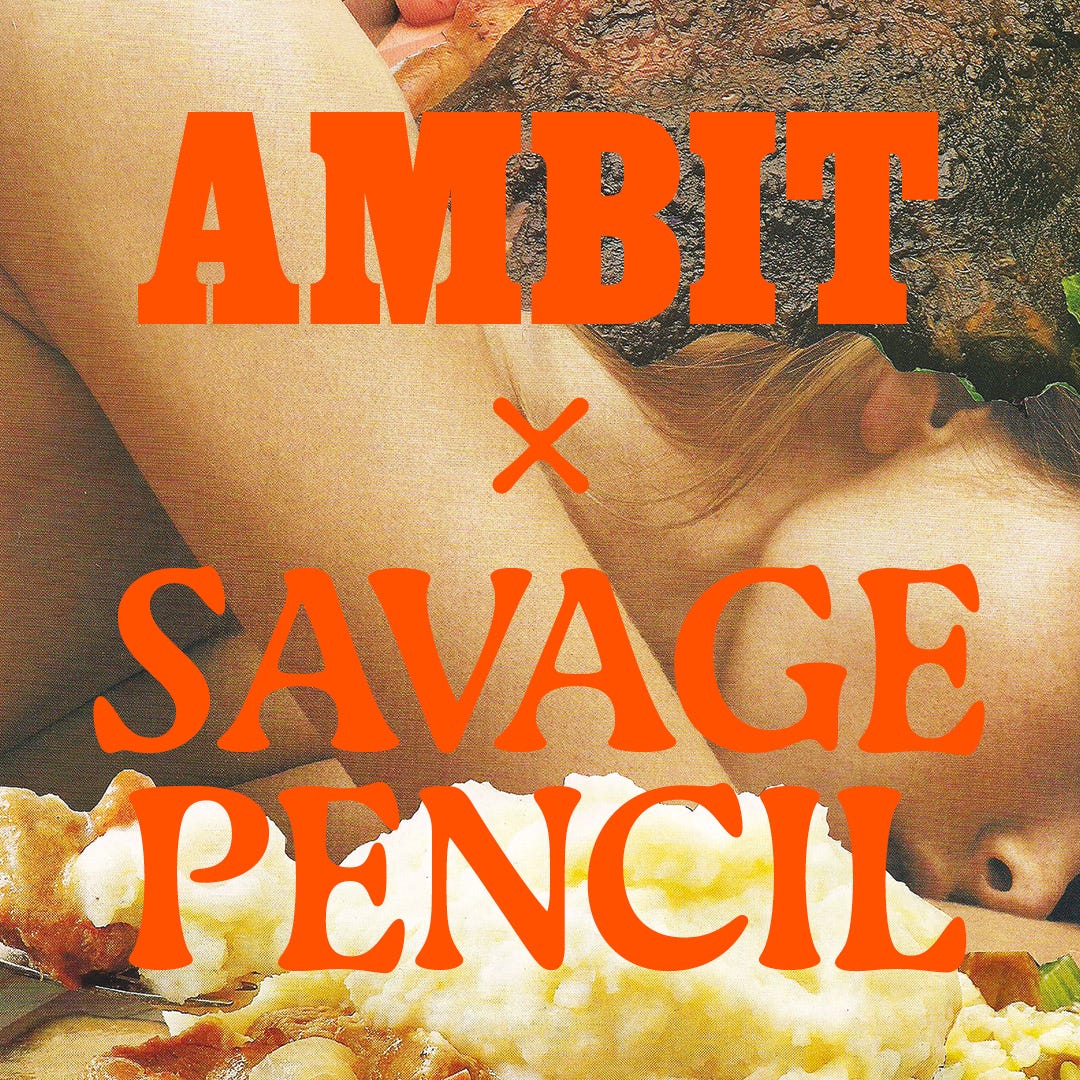

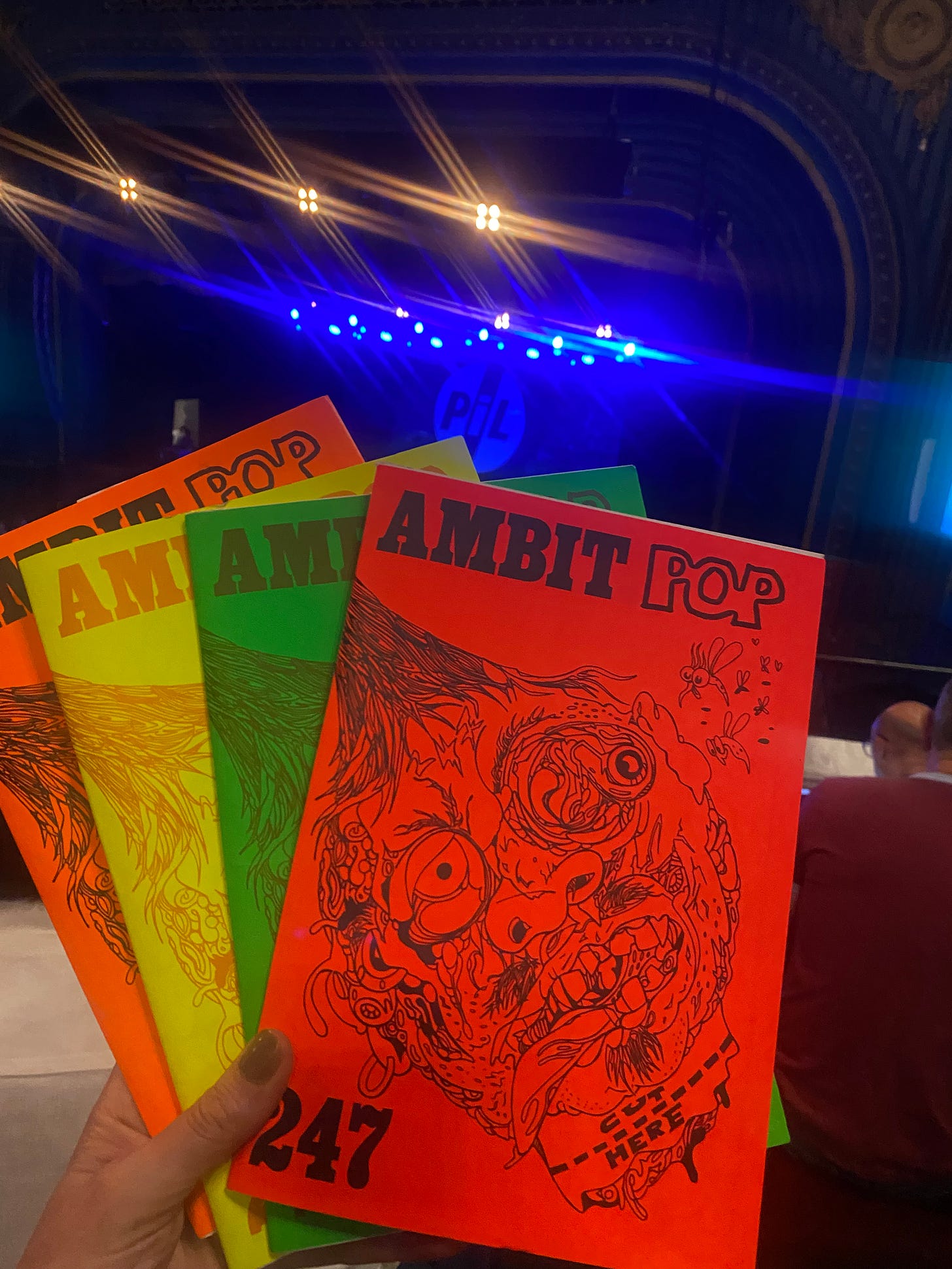

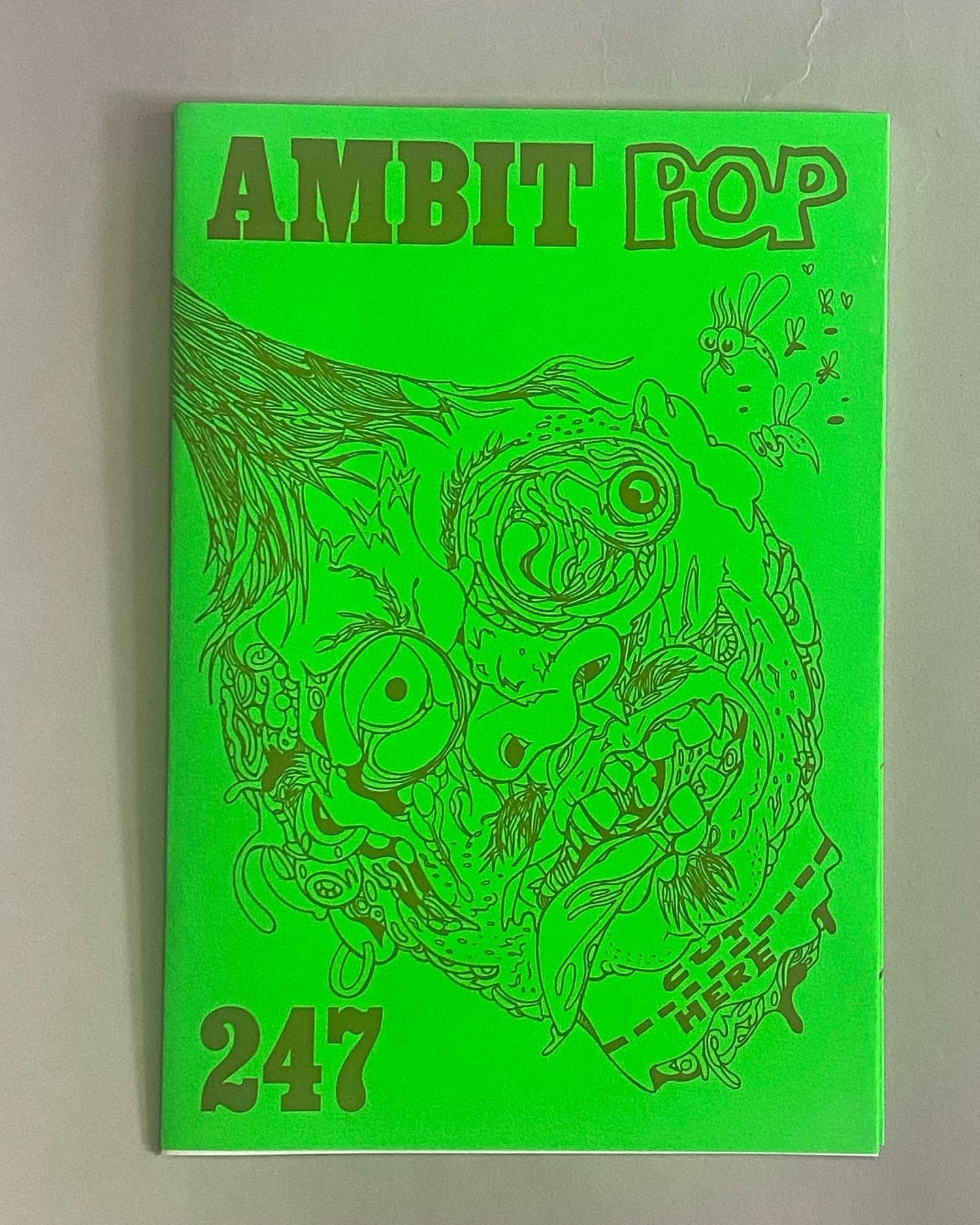

Martin DIYed the magazine from the home he shared with his Oxford University sweetheart, Judy Bax whom he married in 1956 (who died at 82 in 2015). It was whilst in the North London maternity wing, when Judy was giving birth to Ben (the eldest of three sons, followed by Alex Bax (who runs a charity for homeless prisoners) and Tim Bax (creative), collectively offering seven grandchildren), that he met another father-in-waiting, the young Mike Foreman who proceeded to work as Ambit’s art director for 50 years (whilst also moonlighting on titles such as Playboy, The Guardian, designing many hundreds of book covers). Foreman began the practice of introducing RCA students, such as the debut publication of drawings by David Hockney to the cover, and another student, Ralph Steadman (templating much of the work he did with Hunter S Thompson) alongside creating many artworks himself. There’s a podcast we recorded with Soho Radio and this original team after I was enlisted as editor in 2020, with Mike Foreman, artist Ken Cox, designer Alan Kitching and my designer Stephen Barrett. The original Ambiteers (as Ambit’s second editor, Briony Bax coined all contributors) were rather shady about the notoriety the magazine gained first in 1967 with the Sex Issue, and then with the Under The Influence competition for work written on drugs, which led to the Arts Council’s demands for proofs to be unforthcoming, and cries in parliament for the publication to be banned, which followed a withdraw of funding, despite the prize being awarded to Ann Quinn and her work written on birth control pills. This led to 1968’s 37 newspaper issue edited by Ballard, featuring Burroughs, and frequent contributors such as Gavin Ewart, Anselm Hollo, Edwin Brock and Michael Horovitz, and my own Pop issues, guest edited by Lias Saoudi and Savage Pencil, or showcasing the winners of our annual competitions. Almost a return to Ambit’s humbler beginnings. Number 37 is an issue I had to hide from a police officer, as the cover adorns a picture of Hitler like a Siouxie Sioux armband in a Jarman film. But that is another story. The irreverence Ambit provided was a perfect platform for spoof news items, small ads, fun, clever, and well-produced enough to last the test of time. It was the quality of Ambit’s design, paper quality and print which gave platform to collaborations and imaginings which generously committed to changing the face of literature, art and culture. Ambit was the gateway to many creatives future careers. The full archive can be found on Jstor, and a few libraries, including my own. What we find through the years is a cultural reflection to a wider culture of the days it was published in. This was always the purpose of Ambit.

Much of Ambit’s timeline is a little blurry for some contributors, the myths that grew from it are held only now in the archive. For example, I was informed by one of the original crew that Ballard was recruited when Martin visited the Atrosities exhibition in Drury Lane in 1970, the archive clearly demonstrates collaborations were being published for five years before. It’s reported that intoxicated guests splashed wine over three crashed cars (one was a Pontiac) at the New Arts Laboratory where a topless woman filmed the opening. Whether that topless woman was Euphoria Bliss, a mystery brunette who appeared on the cover of Ambit and danced at parties, I am yet to confirm. Although Ambit’s crew can’t take credit for an exhibition bearing Ballard’s name, few events exist in vacuum, and Ballard’s exploration between the unconscious links between sex and the car crash which encouraged his novel, Crash, was templated within the pages of Ambit (see Eye 52 vol.13). Ambit gave space to play and experiment out of the norms, invigorating those who came into contact. Every issue still contains a point of entry for anyone.

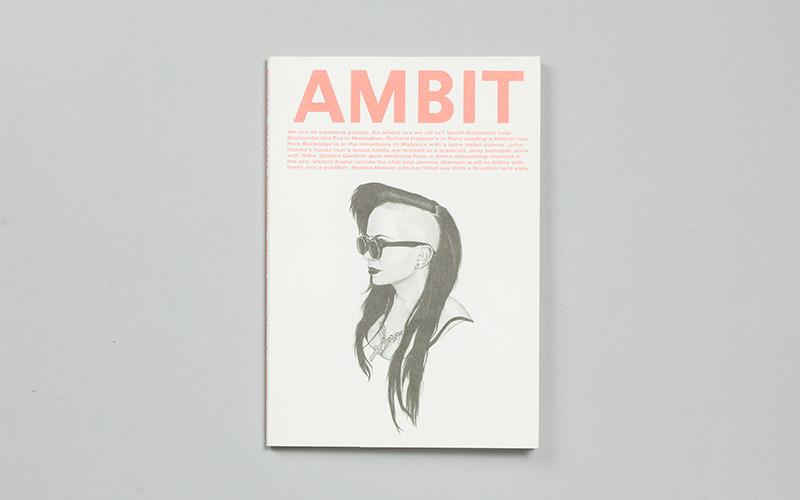

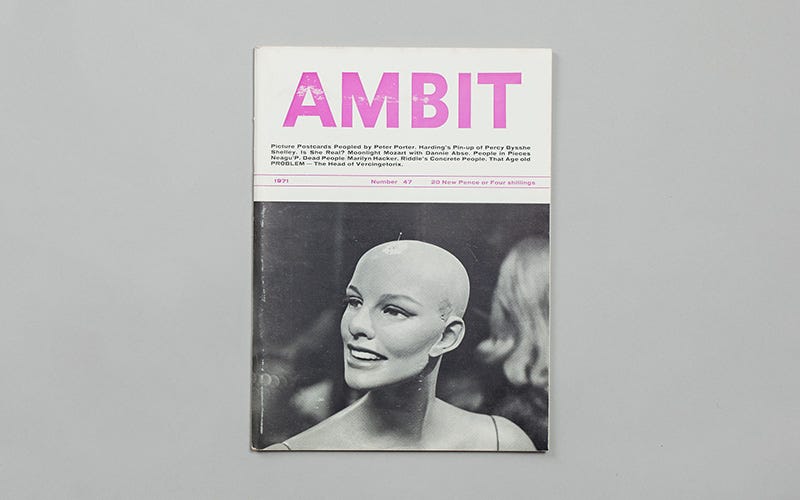

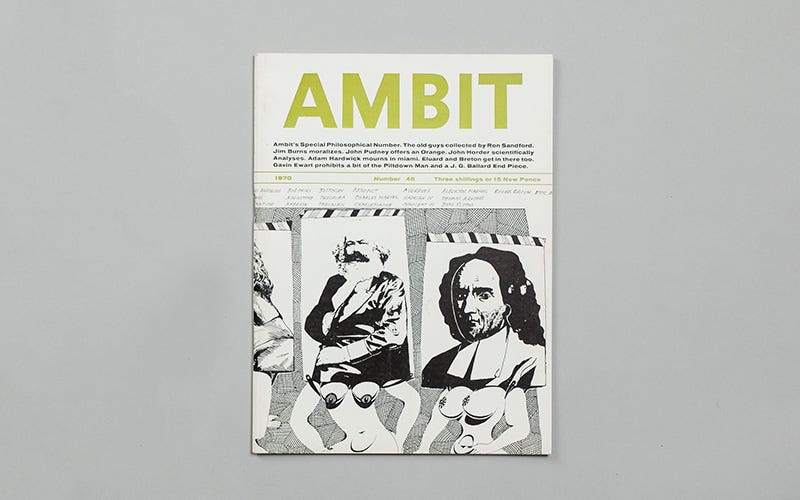

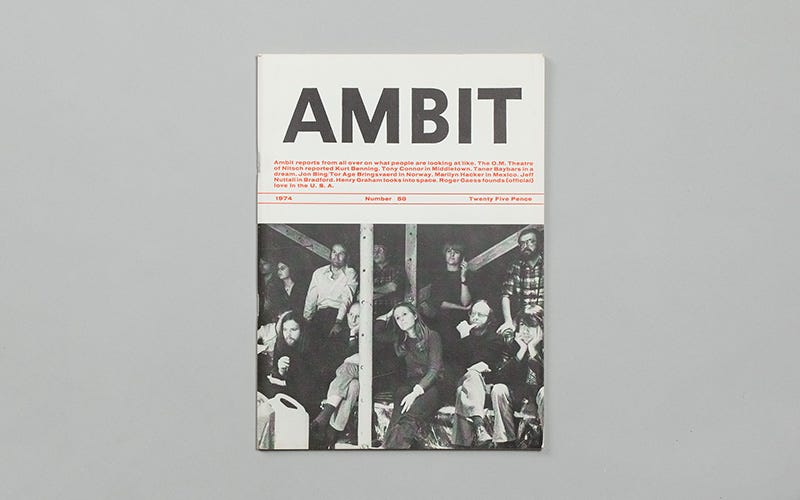

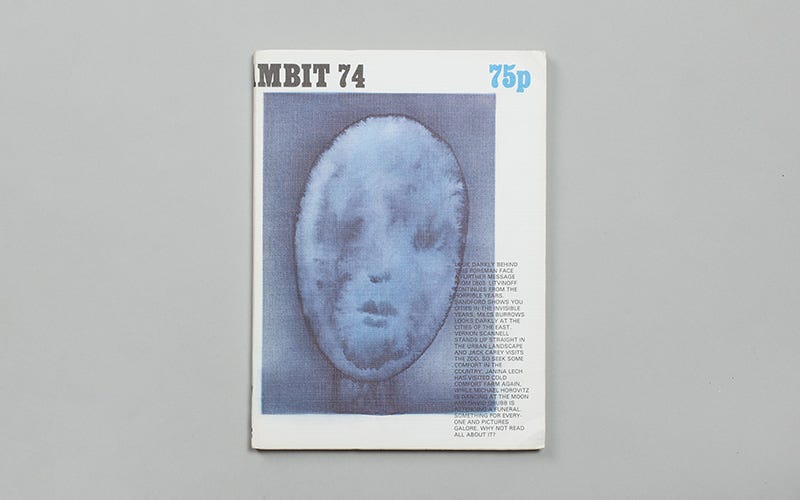

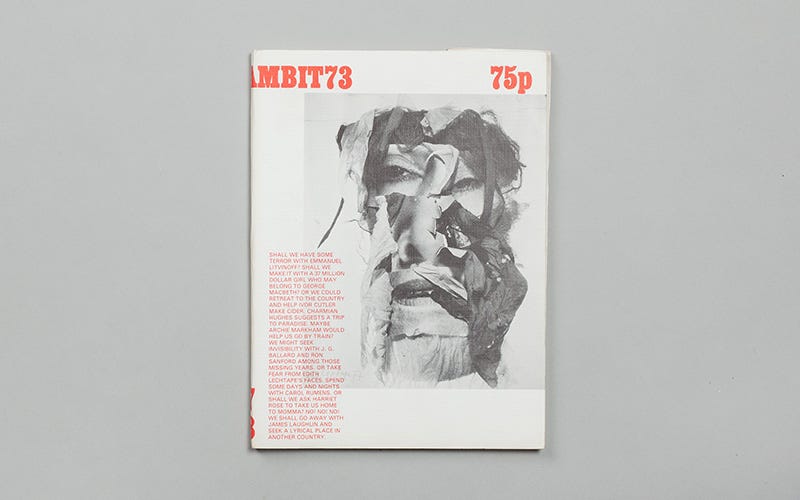

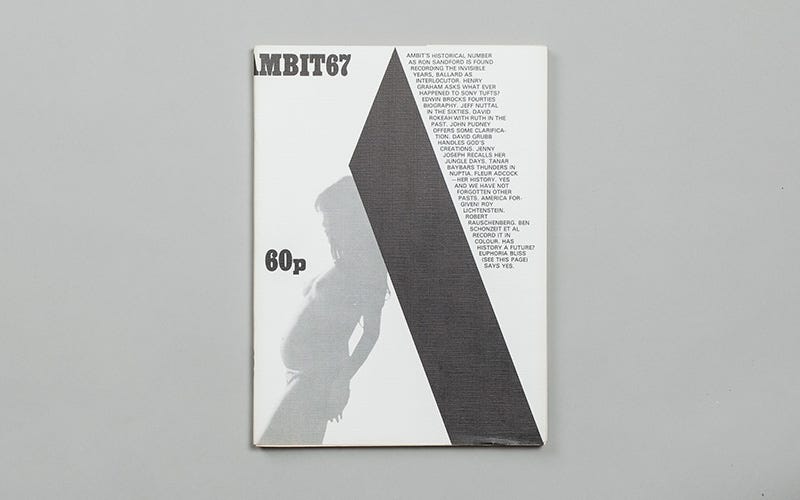

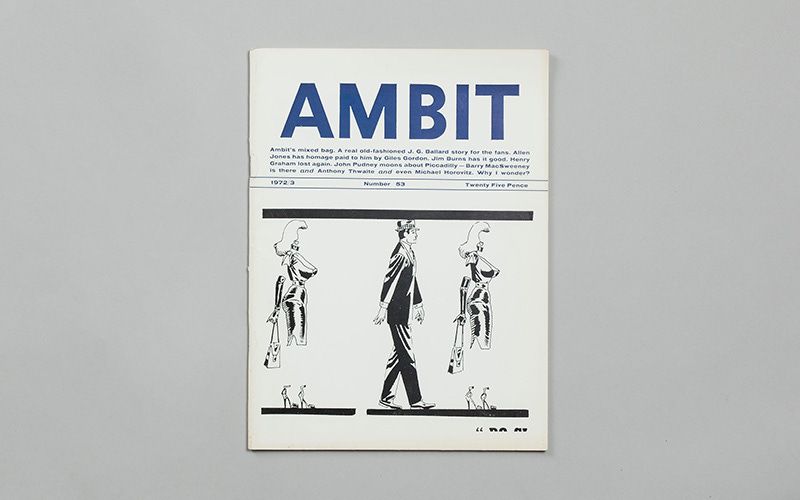

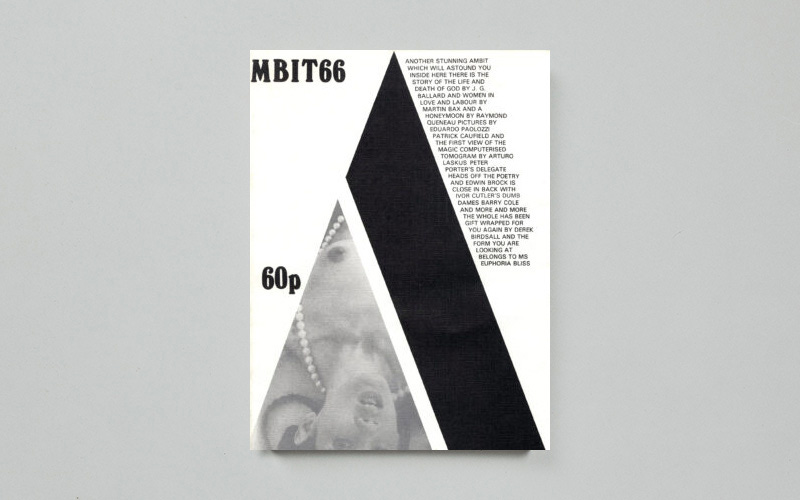

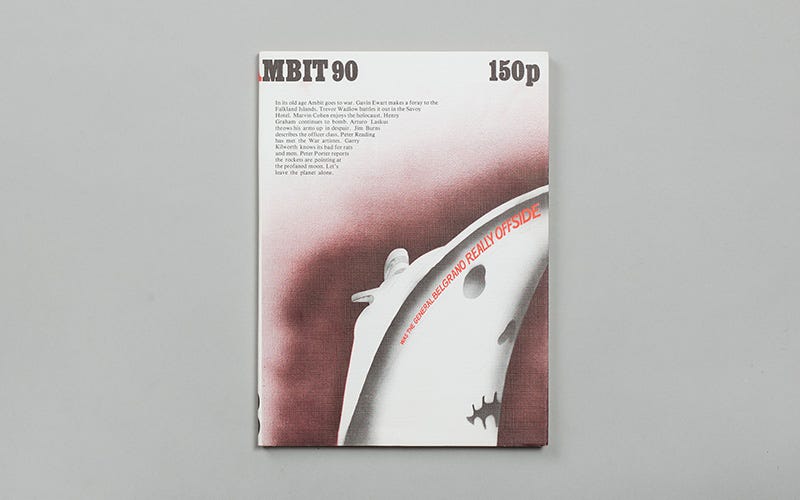

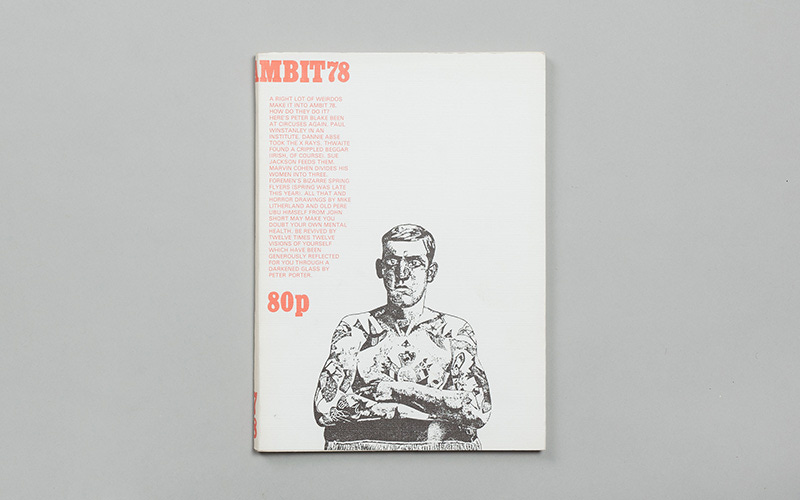

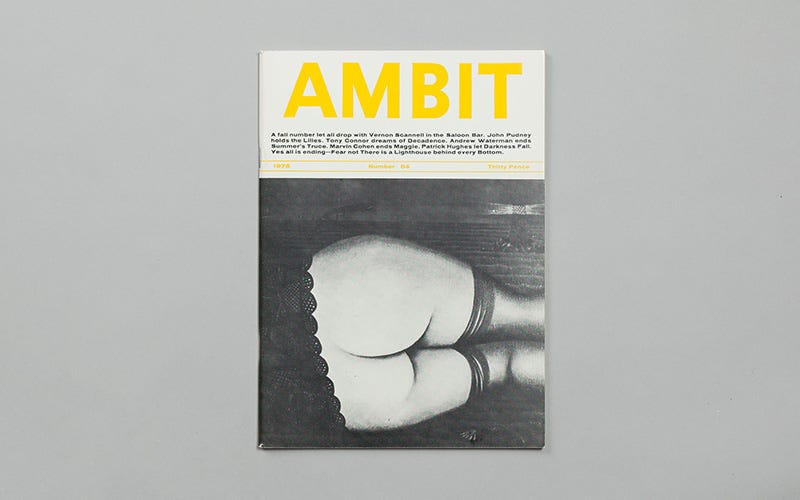

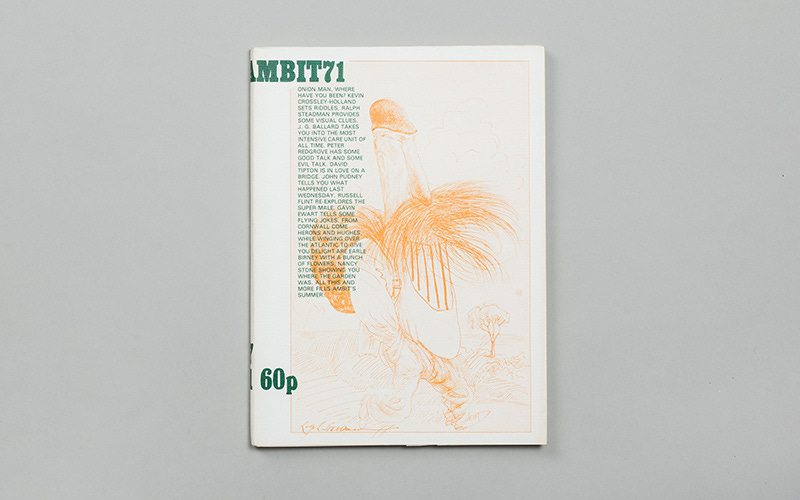

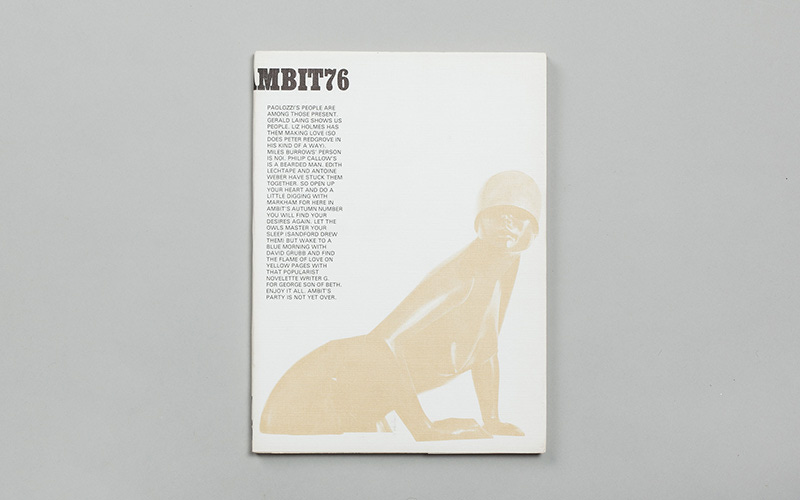

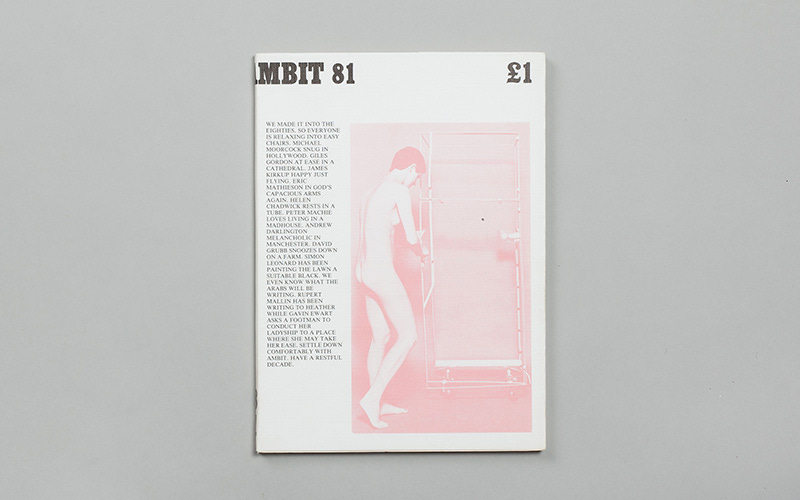

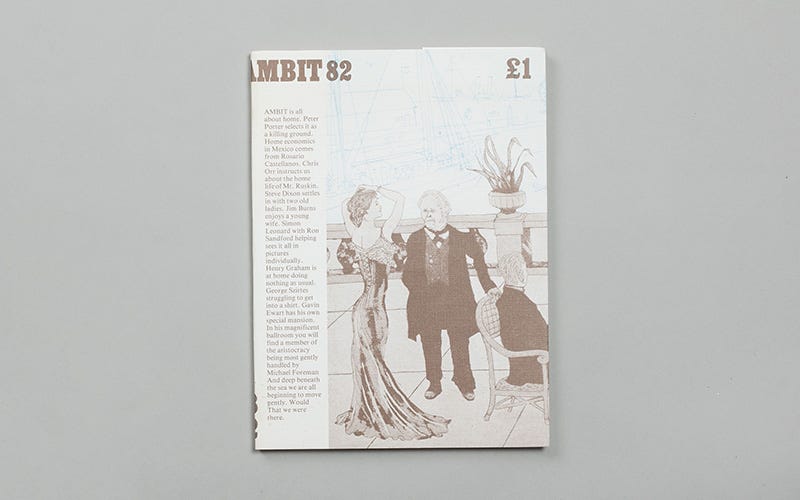

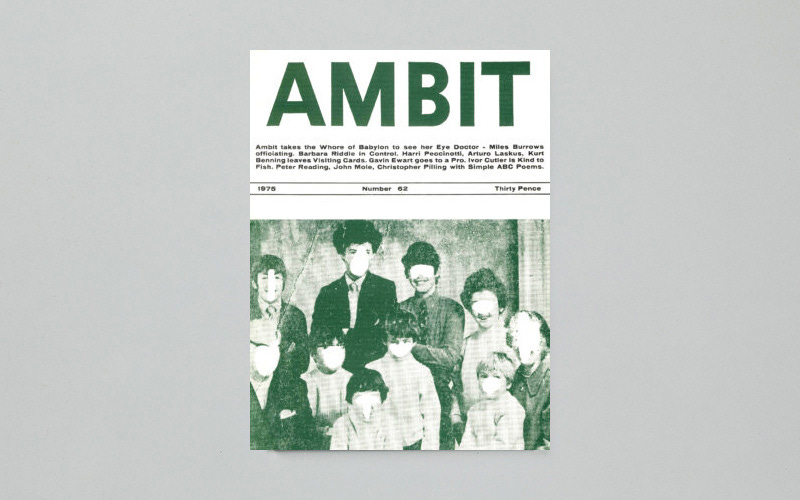

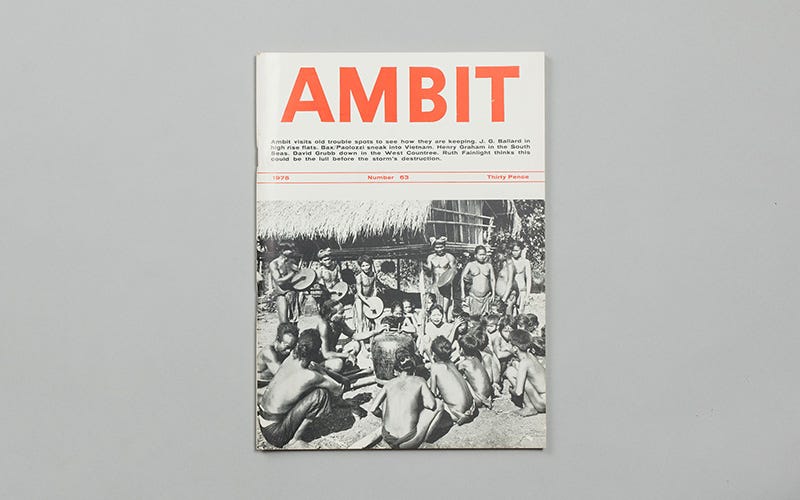

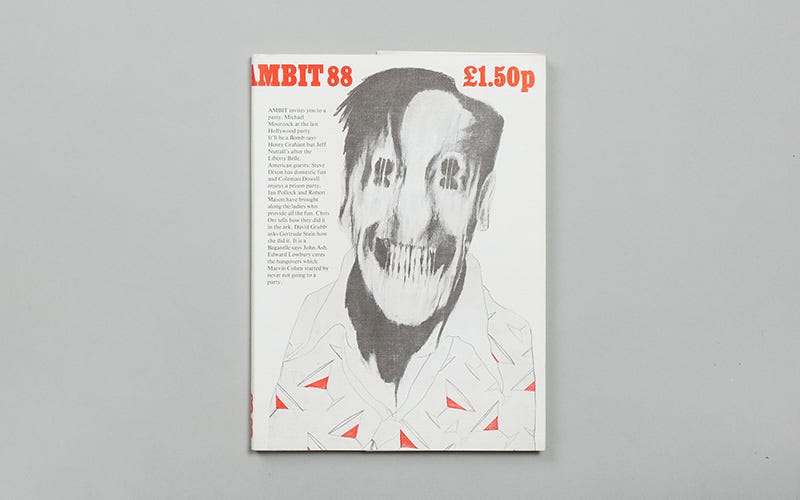

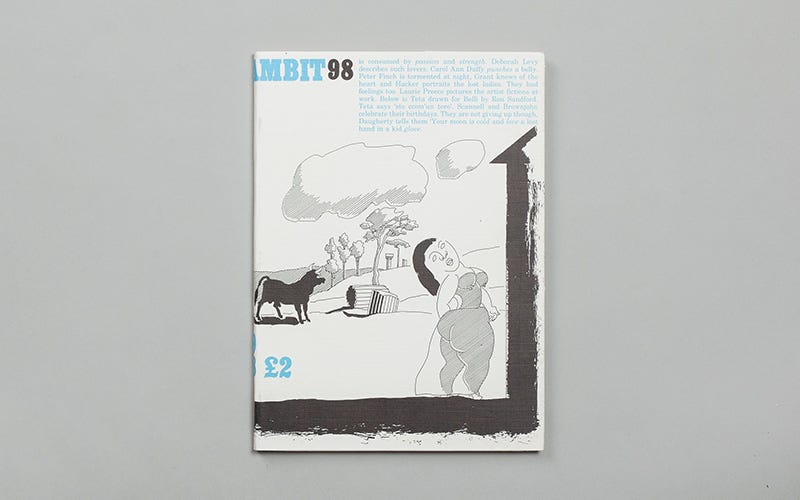

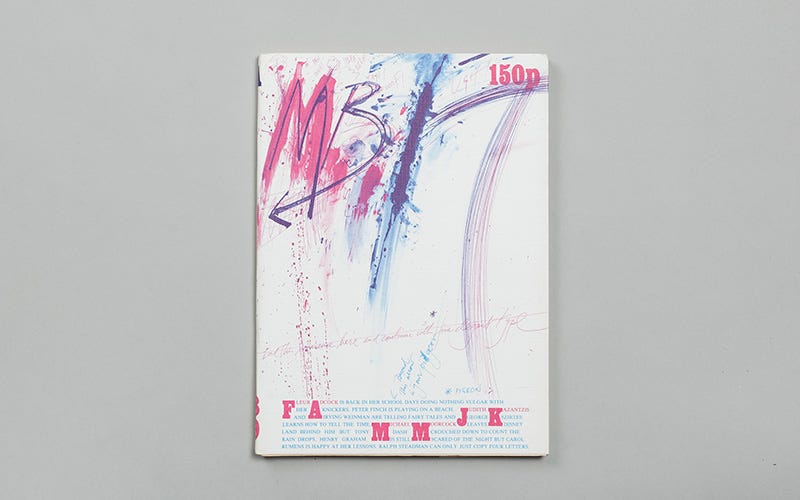

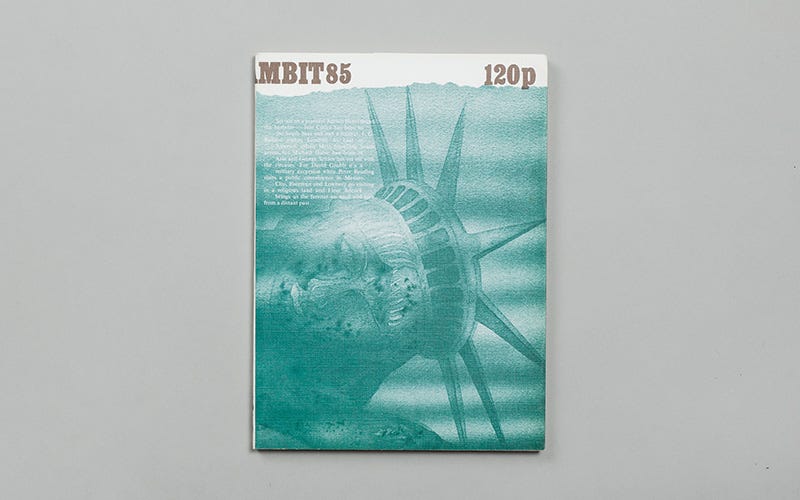

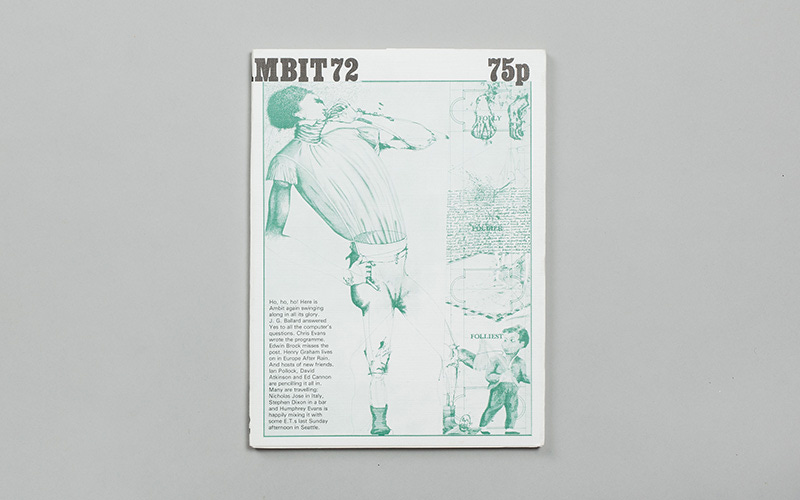

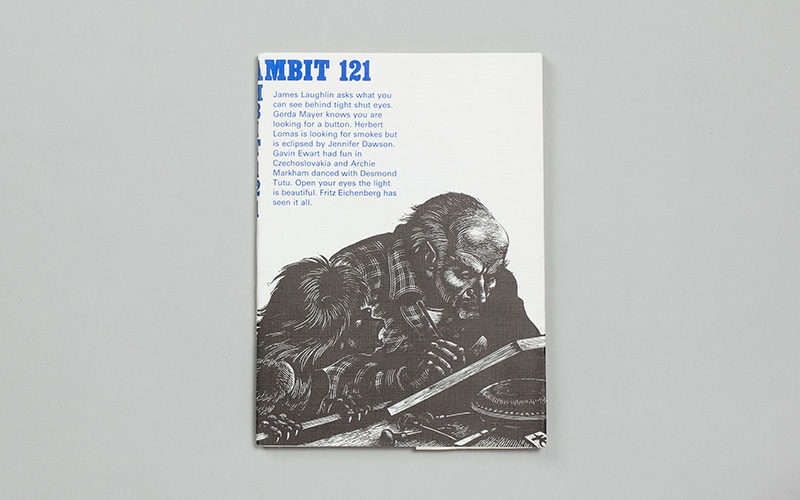

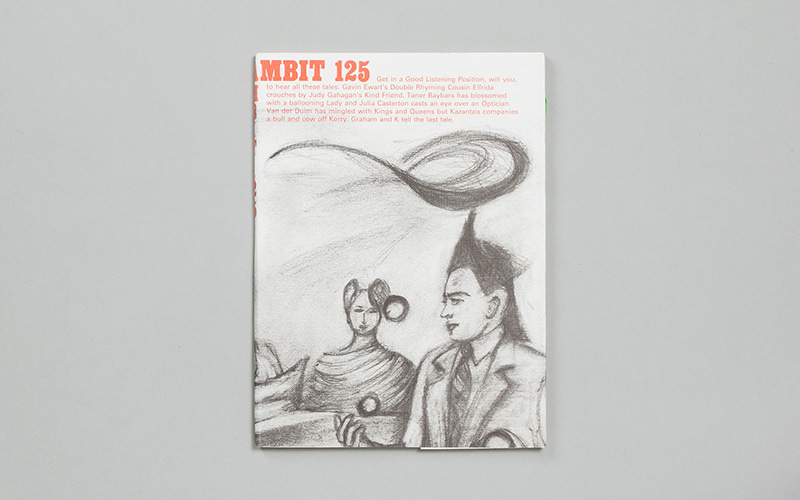

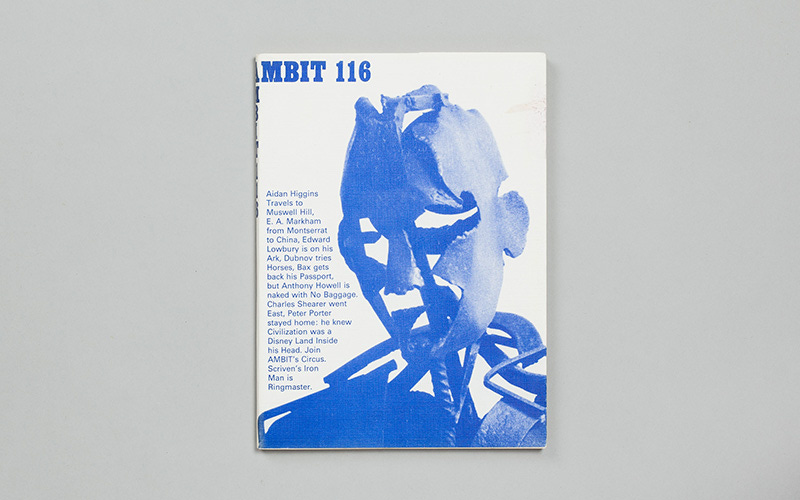

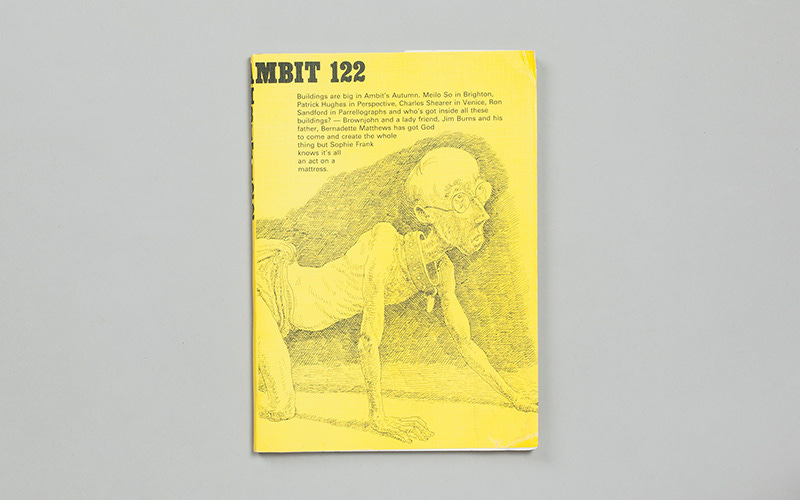

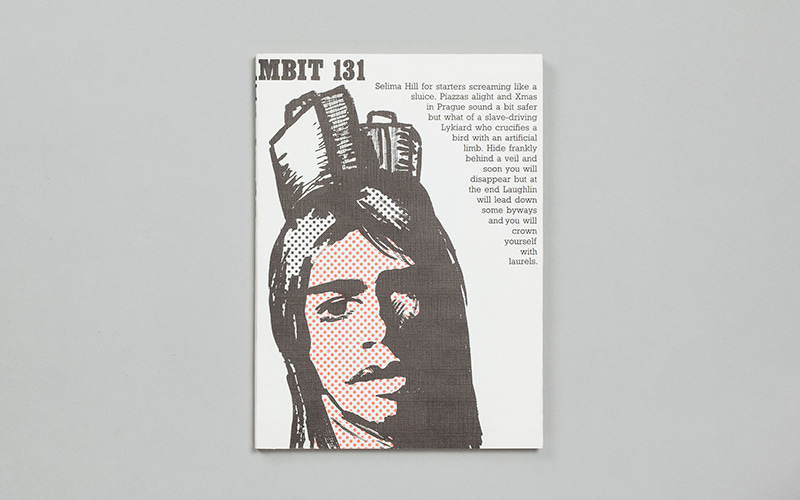

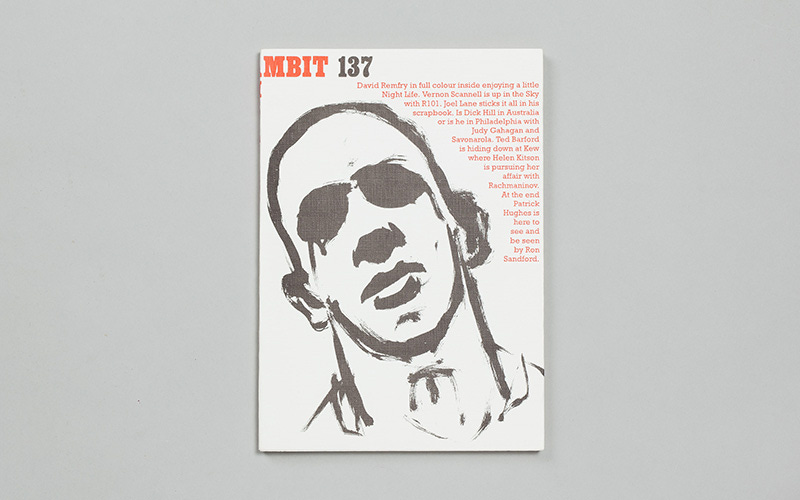

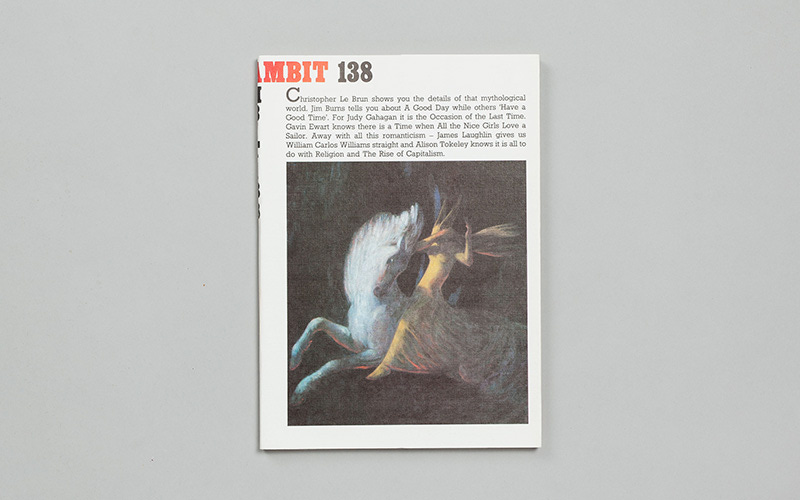

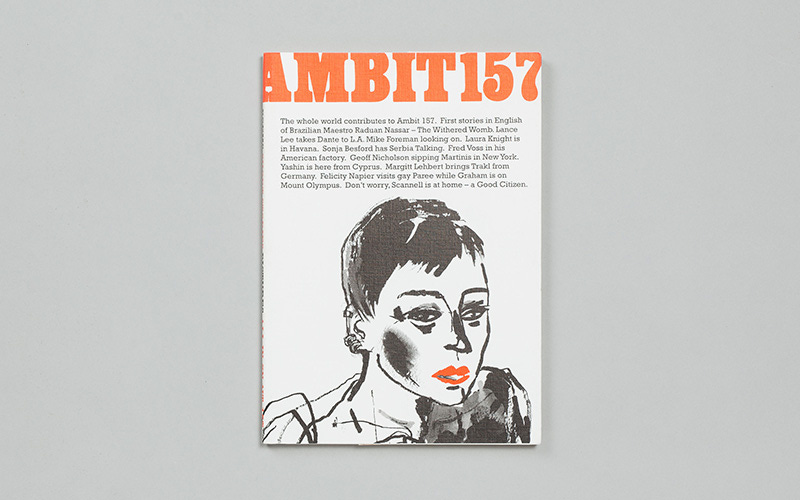

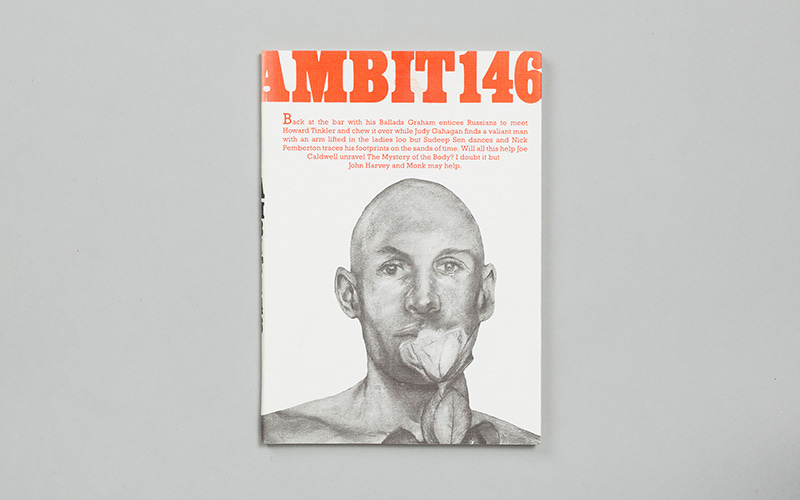

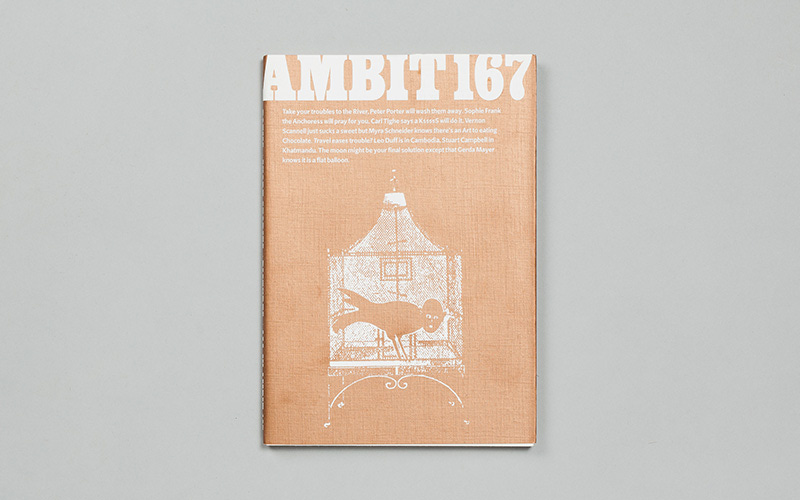

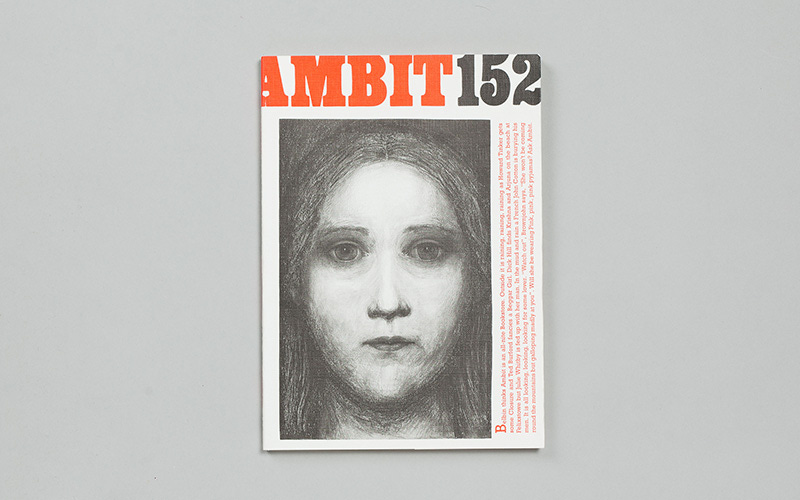

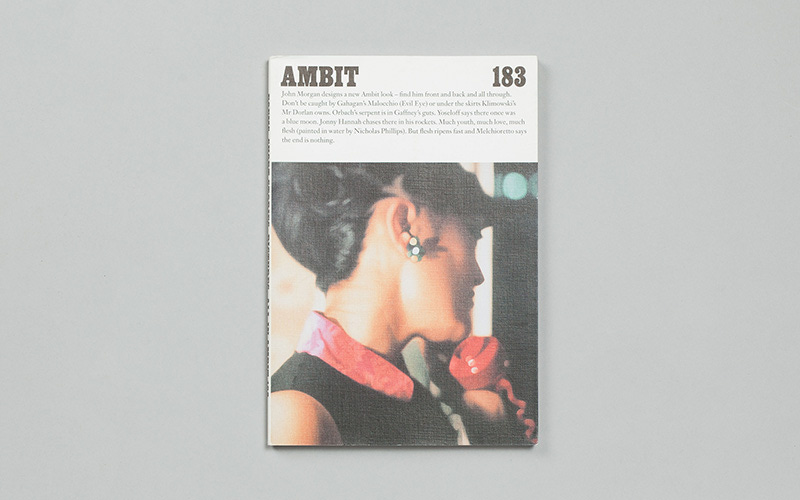

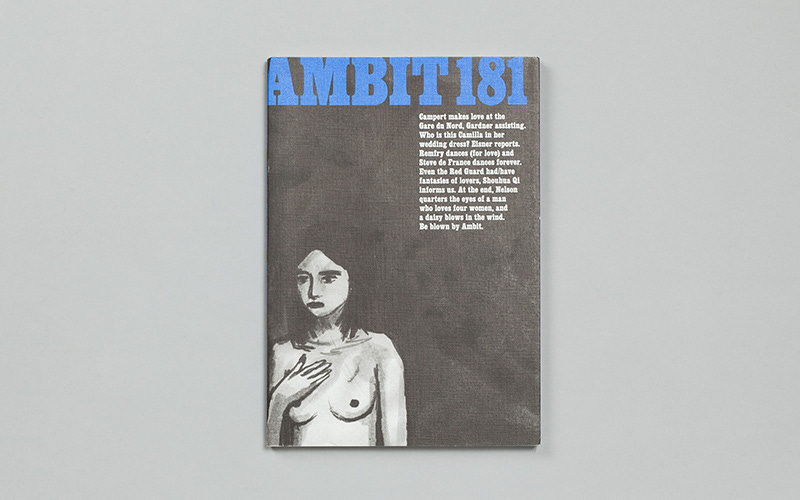

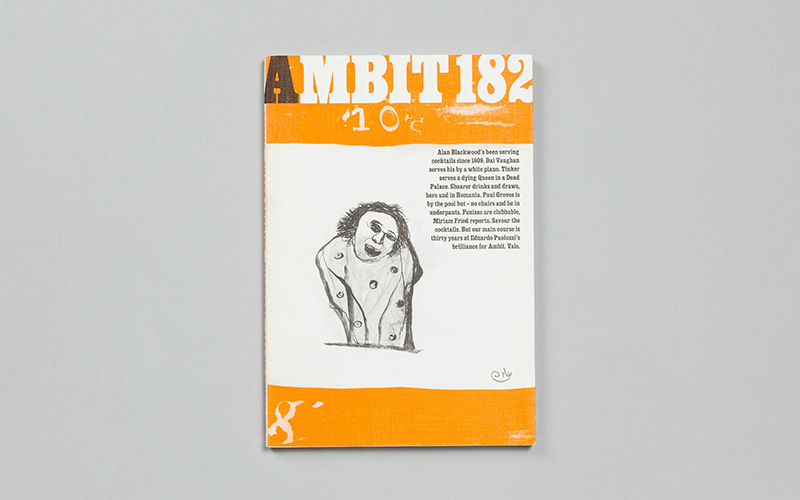

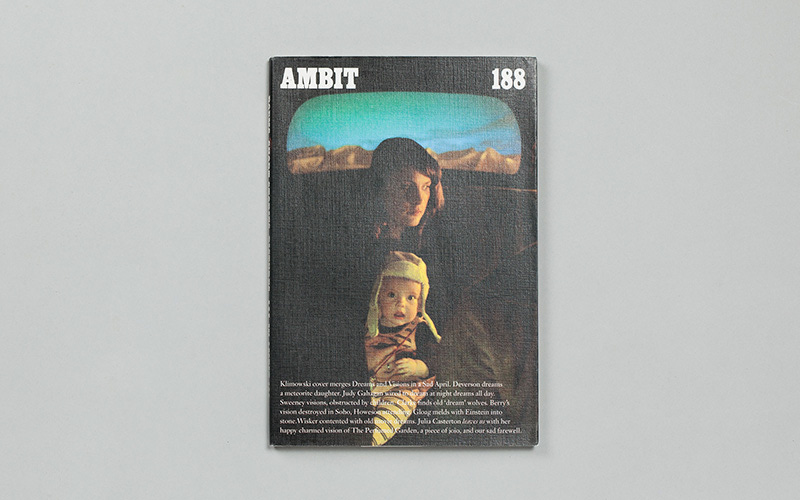

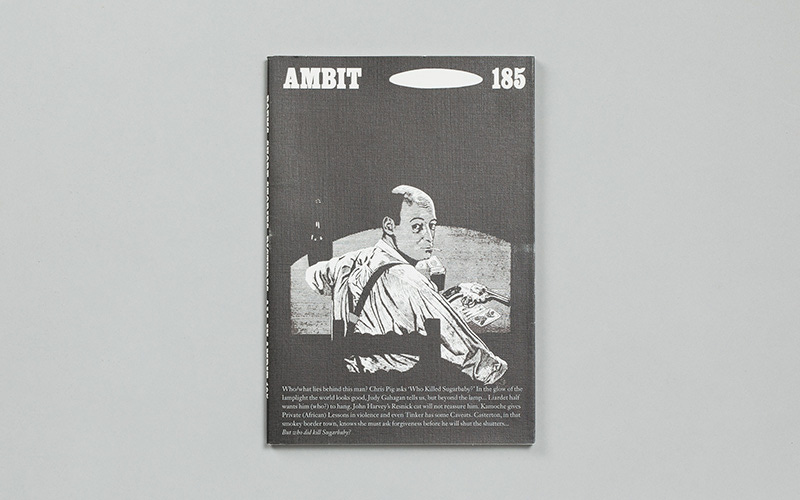

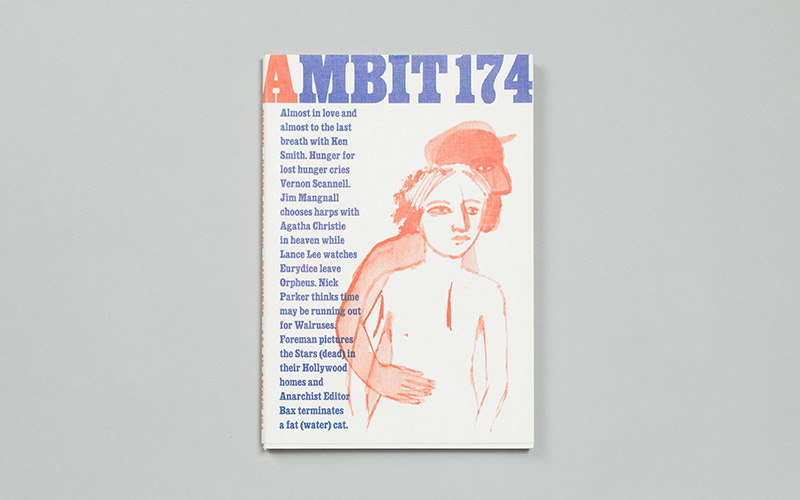

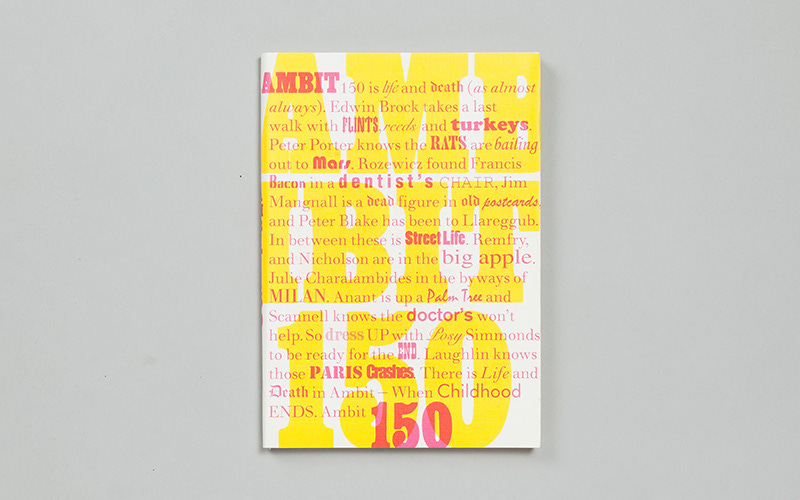

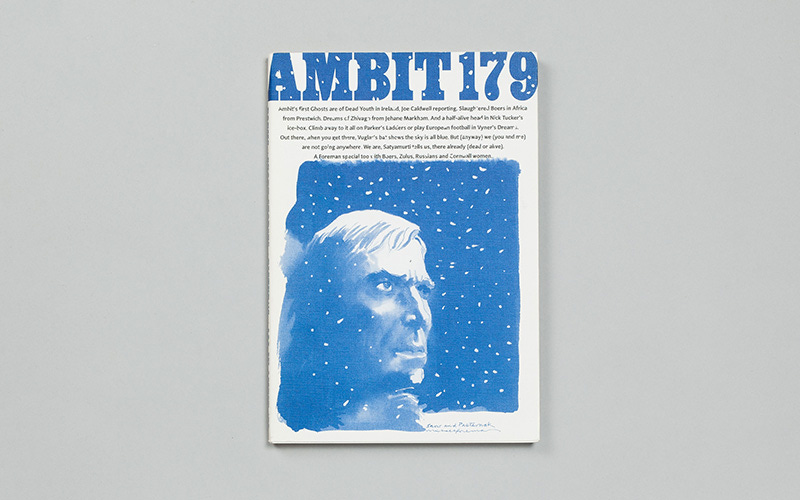

My fave Ambit period tracks the peaks of when it had been running for long enough to let rip, define itself, and not care what anyone thought because it stood in its own lane. Watching the magazine burst from the cocoon of “saddle-stitching” (printing’s code for staples) — after going glossy, and the rare set of Ballard’s adverts running for six issues – going into bound-issues only in the 70s, writers such as Tennessee Williams donated poems (1977’s Ambit 69). Despite what was going on in the underground zine world of punk, it was the mid to late 70s Ambits 66-77 which really gave the magazine solid foundations. They hold The Invisible Years collaborations between Martin Bax, Ballard, George MacBeth and Ronald Sandford, perhaps encouraged by the incredible, classic design enabled by Derek Birdsall, who came on board in 1976, Ambit 65, throwing our mysterious Euphoria Bliss on the cover, booming: "White space is the lungs of the layout”. Born a year later than Martin, he schooled at Central Saint Martin’s and was tutored by Richard Hamilton. His contemporaries were the elder Conran, the Design Research Unit and Birdsall designed the first Pirelli calendar, with an agency set-up with Nova editor, Dennis Hackett. Birdsall founded his Omnific agency in 1983. He was largely assisted by Alan Kitching at Ambit, the leading letterpress artist. Ambit didn’t receive another new look until John Morgan brought the magazine into the 21st century, in 2000, with issue 161.

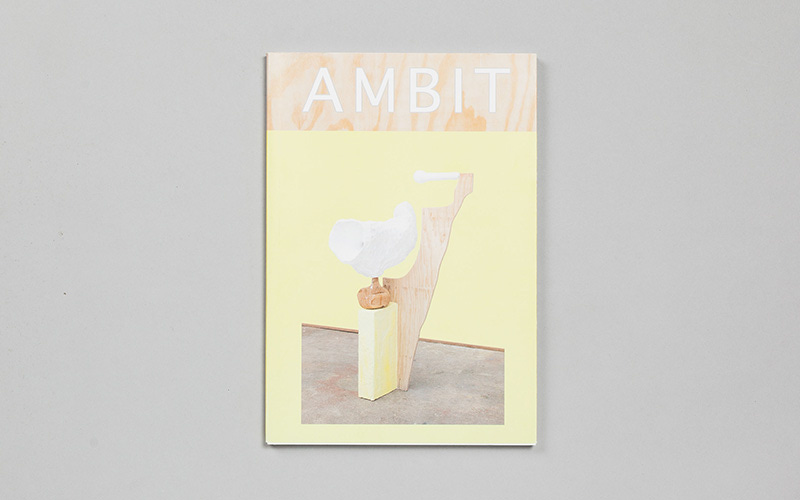

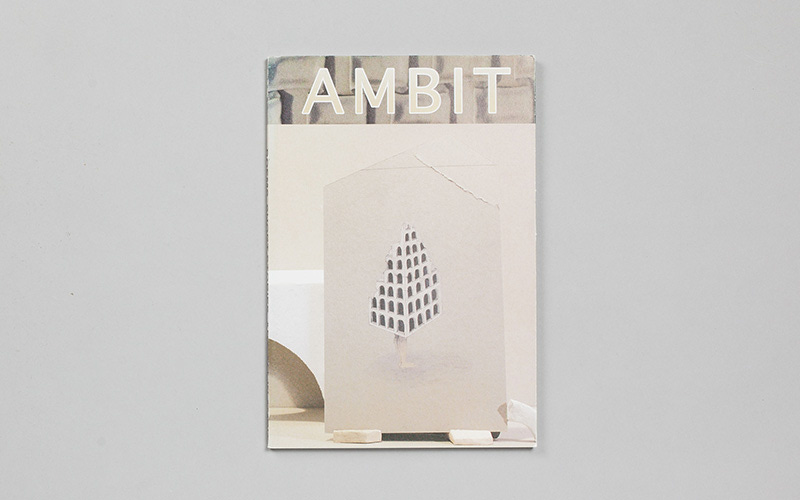

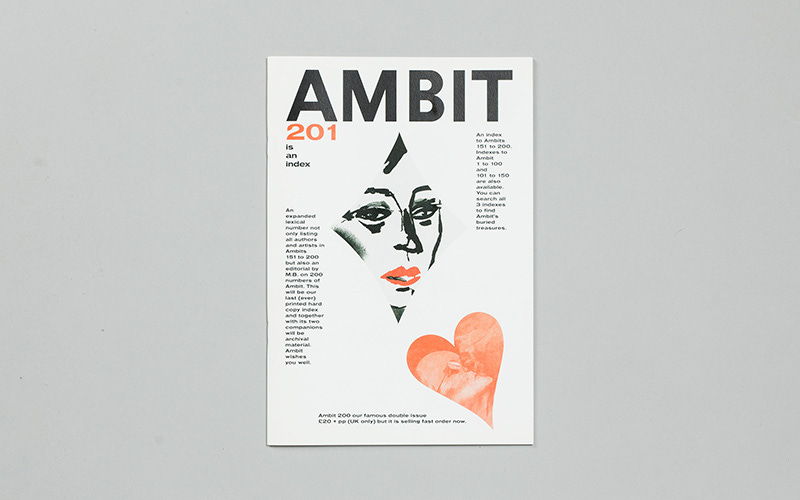

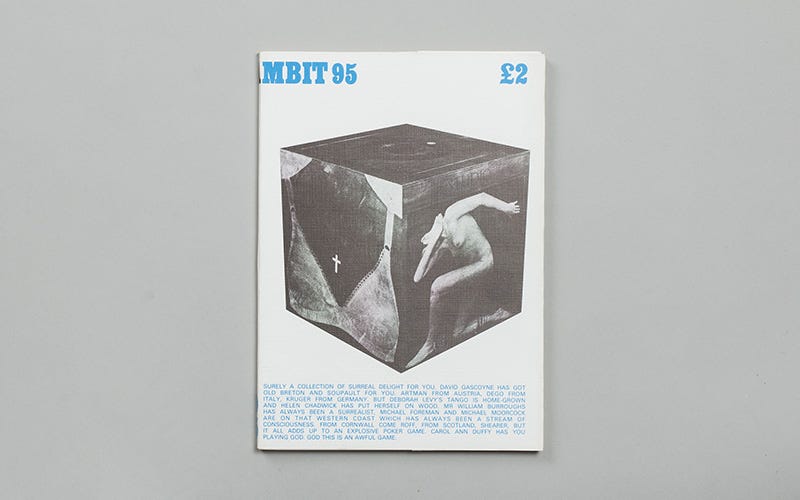

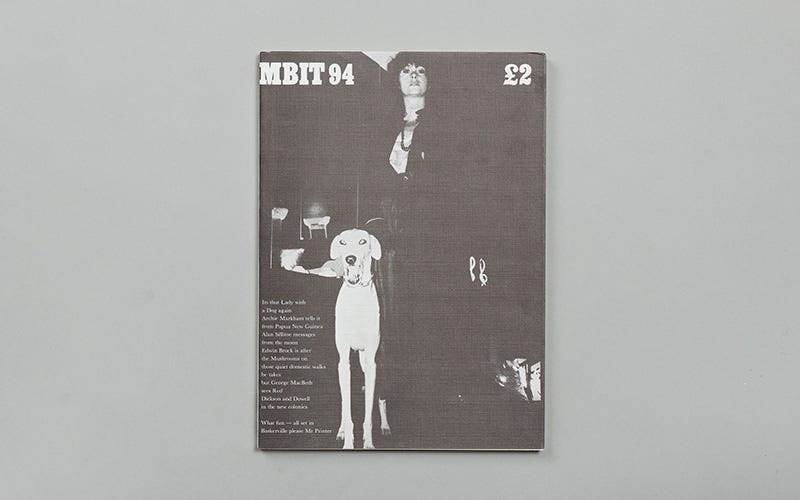

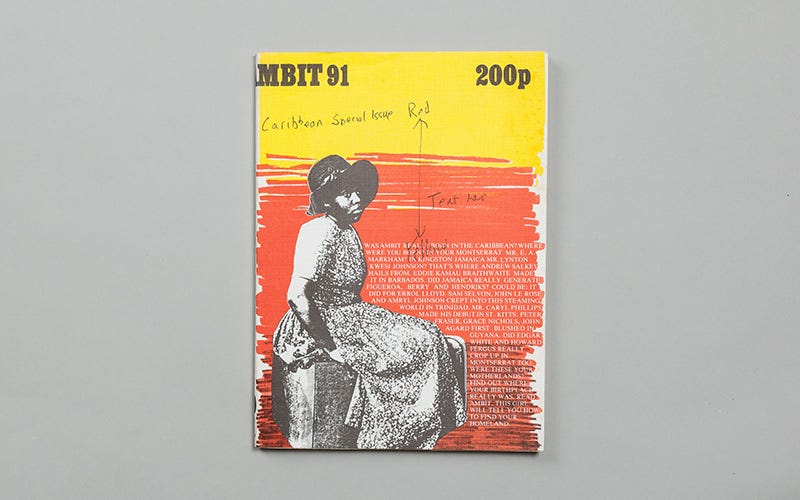

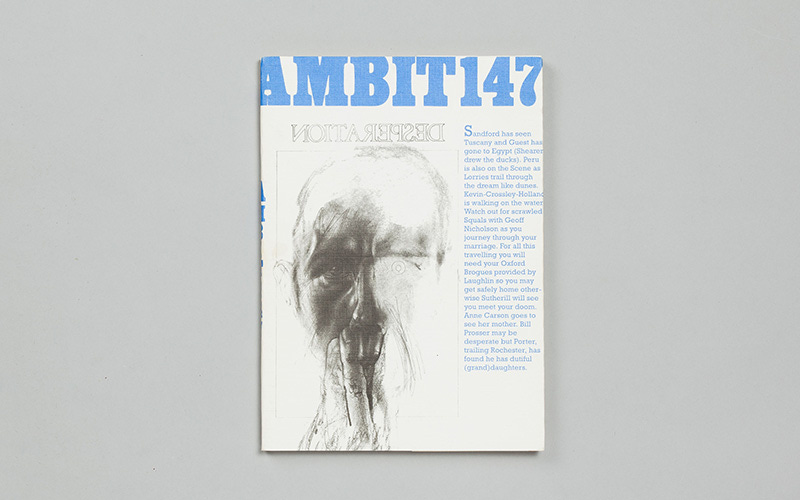

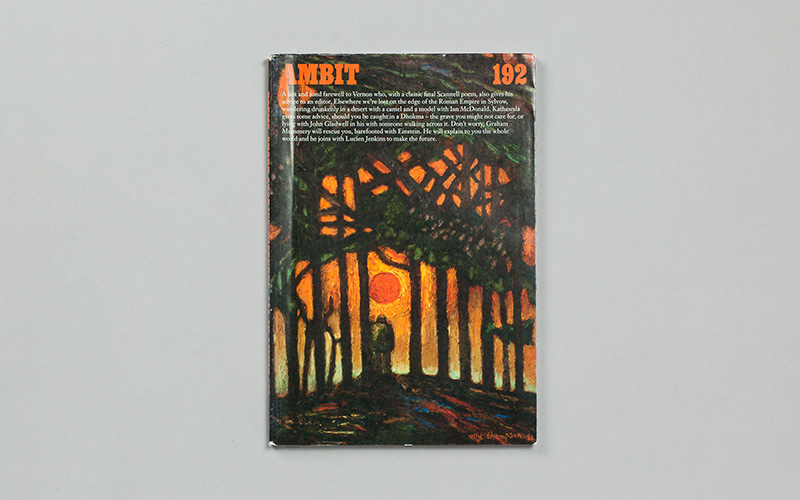

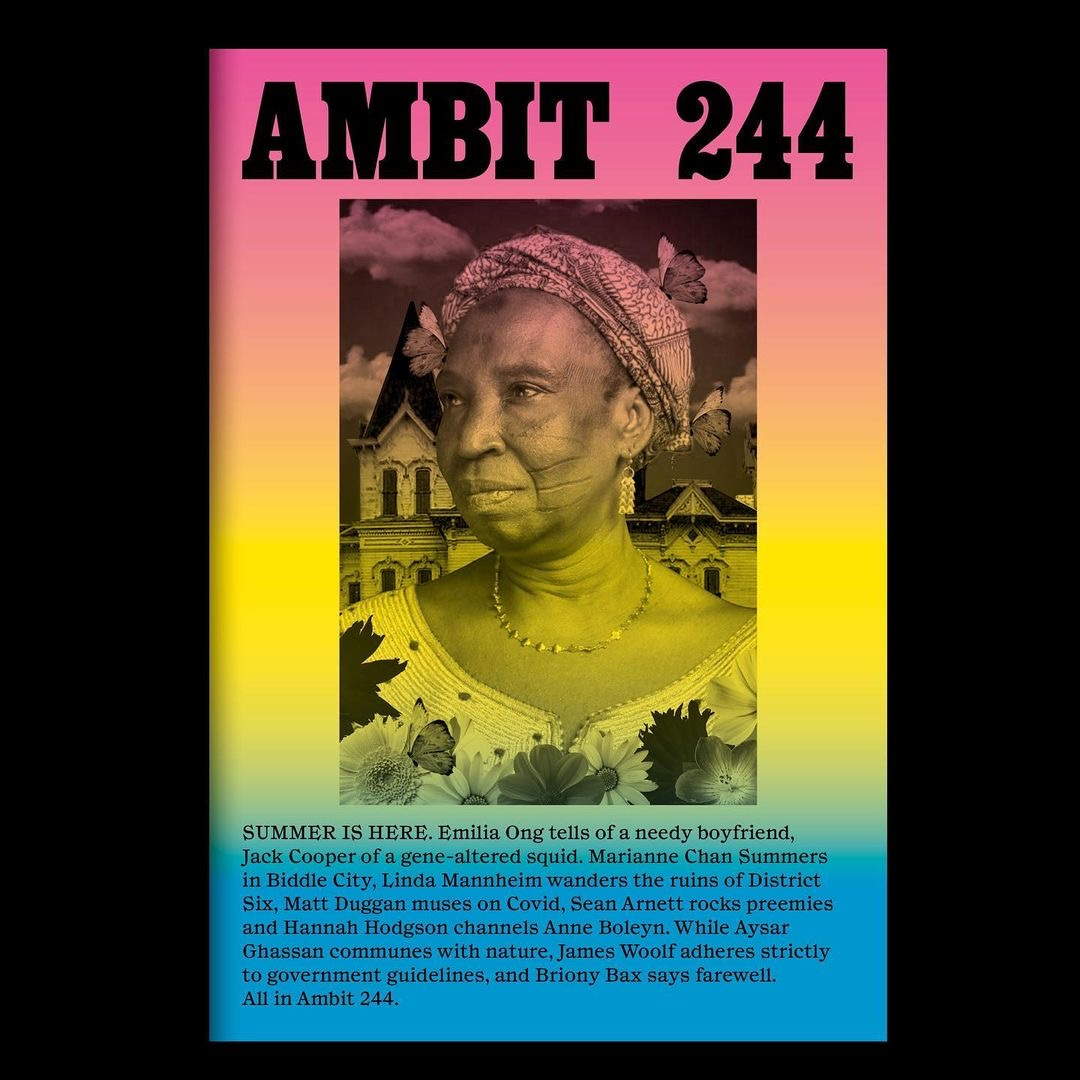

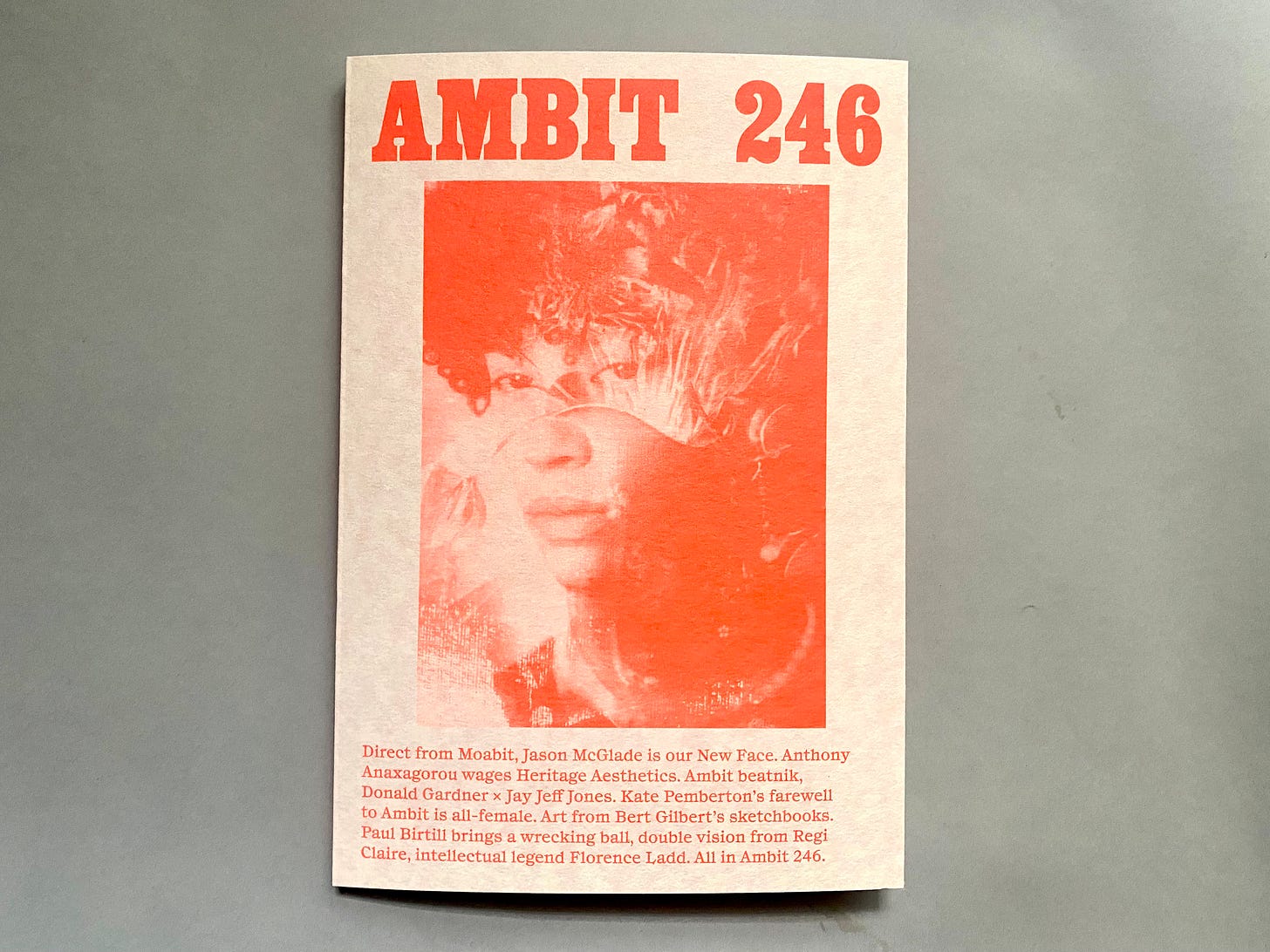

Dr Martin Bax was a man of great ethics, obviously as a paediatrician he was a life-saver, but he carried that sense of honour, grace, duty, and egalitarian principles through the eras of Ambit, doing his best to chart inclusivity and diversity, when creativity was a dream few could afford. All archives lurk with some gazes made inappropriate by modern times but he was ahead of many trends in publishing which have only been addressed in recent years by much of the mainstream media and publishing industry. 1982’s Ambit 91 published Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Agard, and over the years, many women used Ambit to claw their way into the boys club of British arts. Names like Helen Chadwick, Fleur Adcock, Stevie Smith gave hope to women that we could break through. Poetry editors included Carol Ann Duffy who became laureate and was first published in Ambit in 1982. Liz Berry, Helen Gordon, Clare Pollard, and those influencers to a wider culture such as Jehane Markham whom it was an honour for me to publish. Richard Dyer did a lot to invigorate Ambit after joining the masthead in 1985 and pleaded with me not to remove him from the contributors list when I met him at an embassy party. Many contributors owe their beginnings to Martin. When Briony Bax came on board she increased the range of voices again. She took over on 214 till 242, and I had a few issues in transition, presenting the beginning of what tragically became the end of Ambit, with Stephen Barrett. The latter issues introduced me to the traditions, largely managed by Kate Pemberton who first appeared at Ambit in the 90s (helping Martin on his memoir — which is away from me, in a storage unit in Camberwell, but definitely worth tracking down for trainspotters), with production by Michael Smith (a yacht rocker), and a younger Olivia Bax editing the Art, bringing forth many female artists, and Olivia establishing herself as one of Britain’s foremost sculpteurs.

Ambit’s ambition swashbuckled into battle with the belief of youth and became the most stolen magazine from Harvard Library. There are worse ways to spend a life. Walking many more worlds than most existences touch the sides of, as a father, husband, doctor, publisher, editor, author, Martin’s own writing of novels such as The Hospital Ship, which he gave me a copy of (Cape/New Directions 1976) and Love on the Borders (Seren 2005) meant his own magazine efforts received more attention, yet his avid love and performance of jazz led The Hospital Ship to be performed by the Vietnam Symphony and played on BBCR3. By having access to Lavenham Press, able to fund his desires away from the stresses of troubled children, he effectively became responsible for facilitating an entire movement in publishing, unassisted by regular channels, his independence was threatening. He struggled with the academics, really having issue with the Ray Bradbury idea that universities could create writers. He was a punk arse motherfucker till the end. Glory be. He created his own world, in the same way only some artisans can afford to join the guilds of greats. Or wish to. Or could ever dream of being eternalised in. Cementing the names of everyone from Ivor Cutler to Deborah Levy, Peter Porter and Alan Brownjohn to the British canon. The feat of continually publishing quarterly editions for the best part of 64 years, was a direct challenge to the guardians of fourth estate. His own gatekeeping pre-empted Forward Prize dreams, and competitions such as The TS Eliot Award receiving (possibly unjudgeable) volumes of submissions. Although we received 3000 submissions for my final issue, many more than what I began with, I trusted my judges to select the finest. But as Travis Elborough always said to me, it was never my magazine. It was Martin’s. I sent Ambit the first short story I’d ever written, anonymously (albeit with a peacock feather), and it was selected for publication by Geoff Nicholson (whom there’s a great interview with here) who was in from America, taking over the prose editing from JG Ballard (who had little time for poets). That first night of our acquaintance, meeting Geoff whom I’ve since met around the world, Martin told me 2000 words seemed to be the cap on what an audience could bear listening to, after I suspect I went at least 100 over. Ambit had the tendency to go too far too, but although I was never in doubt I was a writer, the anonymity of submission felt rewarding and it was something I continued to offer to all published, I hope, in my short reign. The experience of debut publication felt like I’d made it through to the more elitist world of publishing, away from having to explain myself with the hustle of being a bit media, as the “Loaded Girl” or former DJ partner of Irvine Welsh (as I am now!). It felt like my words had done the talking. At later suppers, such as the 200th edition party, when Martin had threatened to close the magazine, or for his 80th birthday, where I was honoured not only be one of the people he fed, but also contribute to a publication arranged by Kate Pemberton for the last event I saw him at the Chelsea Arts Club, ten years ago. Martin’s generosity validated publishing as a sport of dignity.

From the first cheque that I never cashed in exchange for my first short story called Lyla, about a girl grown in test tube of popular culture, to the last days of Ambit, it was strange I found myself at Anne McCloy’s new Mobilise the Poets night last week at the Boogaloo pub, just up from the old base of 17 Priory Gardens where the magazine was always HQed, and up until its sale last year, supporting Martin’s final days in care, the shelves burst with remnant issues, despite many being stored in the Norfolk home of Briony Bax, who made Ambit a charity and took over as editor when Martin moved into an emeritus role in 2013. Ambit relied on the loving volunteers and people paid in cake and mentorship during all of our reigns, the wives, sisters, and the support of people like Alex Abery who did much of my backend work, posting out issues from Norfolk. I was working with a fast rotation of interns, keen to use Ambit as a stepping stone rather than commit to the greater cause, but relied on the good hearts of poets to join editorial boards to challenge what I could not see. We were all groomed in the Ambit haze of glory. I remember a publication party in Exmouth Market (long after I’d lived there), after reading at the Betsy Trotwood, meeting Martin’s late sister with Jehane Markham, whose late husband had edited with Martin back in the day. Ms Bax passed on great nuggets as countercultural batons to the beatniks and refuseniks and psychedelic underlords who paved my way through the illustrations of subculture shelves which guided me from Ealing Library to become a writer myself, and submit to Ambit:

“When I first met Jim (Ballard), he asked if I were a writer,” she told me. It was the same question I’d asked her as she’d revealed worked in a very glamorous sounding university library on the West Coast of America. She told me the same thing she’d told Jim, “I’m more of a reader, really.”

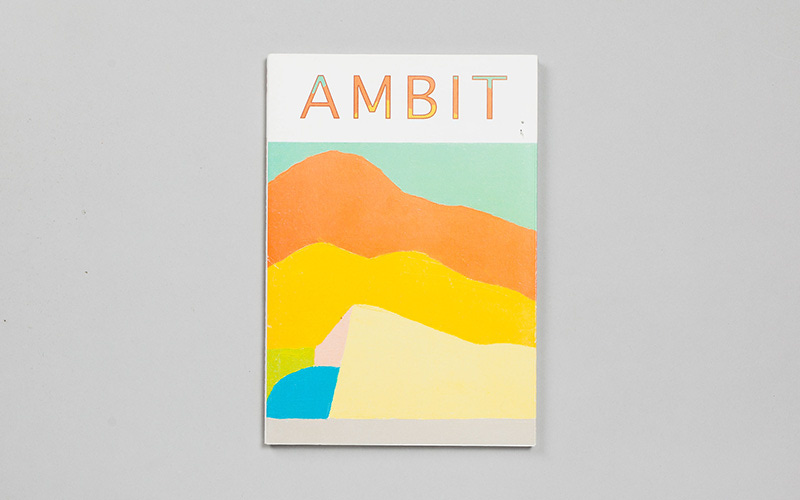

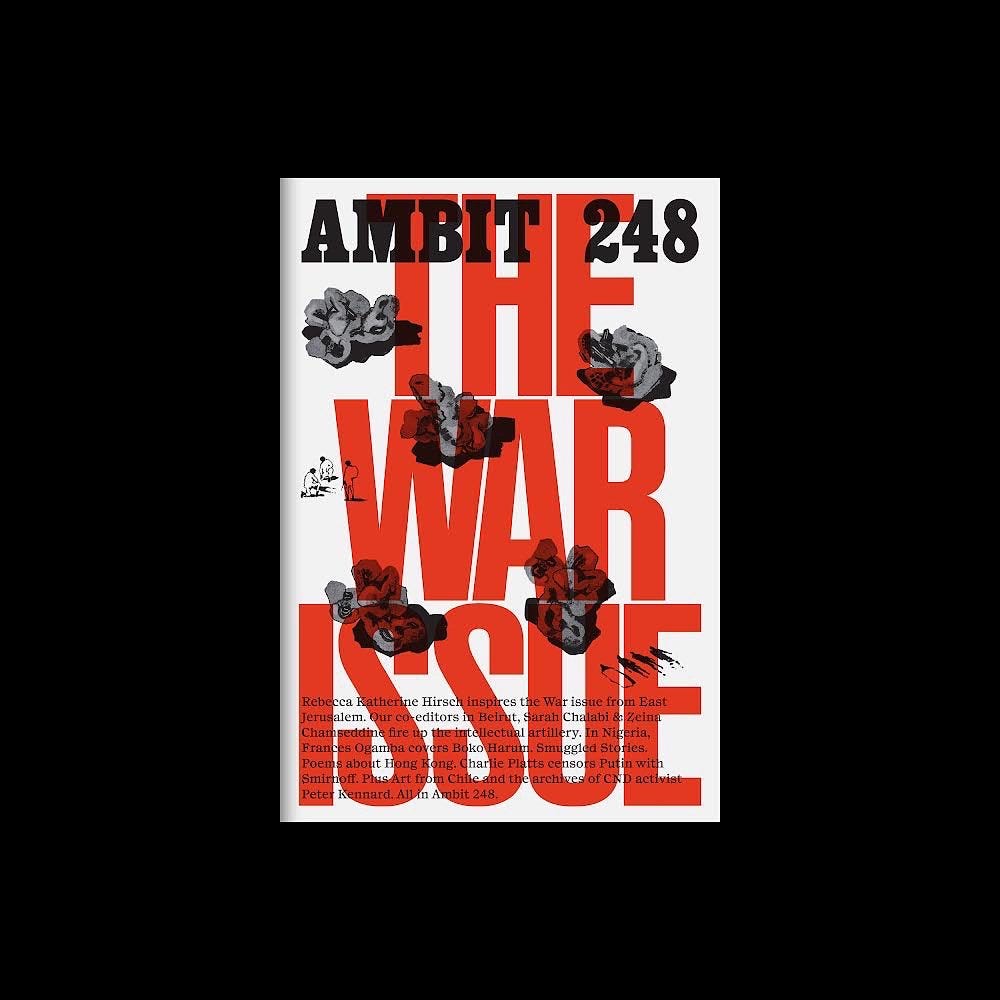

“Well, we writers need readers.” Ballard had responded. As I have since. It was these gateway stories to the greats, the postcards Burroughs sent to 17 Priory Gardens, that made me feel privileged to be a part of the magazine’s legacy, like Martin, its grandeur lumbering in the clouds of greatness above every Next Bright Thing he published since founding Ambit in 1959. I was beyond grateful to be bestowed the honour to rebrand the magazine with direction from the board and my able designer, Stephen Barrett, recommended by the person we named illustration editor, who remained on my team whilst I found my feet. She followed the tradition of recruiting students and offering them publication and demanded money for them, and I also paid her, finding my way further with every issue.

I was incredibly sad when Ambit ceased to be, as I am now. Following the loss of a major patron and a university’s support buying our archive, I was distraught to be informed the finances made the future of Ambit seem unlikely, and with a magazine house showing interest, I recognised that death may come to all of us, but my memories of Martin Bax and Ambit, ripple through my cultural bloodline. I accepted the relief of slowing down on spending all day and all night producing something of the impressive quality of what was achieved by Martin and had time to begin working on my own writing again. Kate gave me a bottle of gin and some chocolate. I don’t think any of the team expected to find someone as passionate as I was, I believed I could make a success of Ambit once more. I doubled subscriptions. But without better distribution, which only comes when you have a stable of magazines, bashing out content for the sake of content, selling mass advertising, the romantic idealism of Art needs to be supported and appreciated by the powers that be. I was just the editor. It was the hugest compliment to have the old school recognise my vibrancy and will to challenge the very dull nature of publishing which led to Ambit needing to be found in the first place. Dr Martin Bax gave it all of his life. As I write here, the inevitable happens to everything in the end, but what a beautiful series of works Dr Martin Bax added to my world and so many others, facilitating so many people, offering hope where there rarely is any. Martin leaves an incredible legacy yet he was floating on what was behind him by the time I first met him.

—

Here’s an excerpt from the first Invisible Years, from 1976’s Ambit 66.

These are the invisible years. The years when the fires behind the skies died down. These are the years when the fantasists decay. These are the real years, the years of myth and reality, the years of focus auad obscurity, the years of bigotry and bedding, the years of breeding and death. These were the years into which the tailless men were born, their eyelashes browned by the heats from the expiring grasses. These were the years when the blues of the moon merged sensibly into the mauves of the morning to yield that incandescence which she - yes Ayesha - bathed in again. These were the years in which the women vouchsafed their men the delectable to touch, the feelings of yesterday wrapped in the minds of to-day. These were the years we felt long ago that summer in Sisyphus. These are the years when the snowcem cements burnt their cores to ashes. When New Cem is born - the concrete of the graveyard and the disaster. The builders quarrelling over its use through the tensile night hoping for survival from the blasts of mourning. These are the years when the windows mewed. These are the years when the widows blasted their names on the starway of the weather men, heating their sons over the vietnamas of Asia. Risking their navels for new seed from the rice river deltas. These were the years when the carapaces of cars no longer kept out the wind. When the exhausts enervated by the environment encapsulated and sporred their orgasms. When the trucks traded their futures for loads that would wrack their articulators. In the invisible years side cars became sites for seedings, back seats went into decay, and the glitter of chromium gave way to the glare of gold plating the tanks of mercury, the oil of the Gods. These years transported themselves, moved themselves, made themselves something finite but unobservable. These are the years when the flyovers folded, shutting like card houses and covering the ground with corruption. When elevators sprouted beyond their homes filling the skies with doors to button open. Buttons on the years touch tenderness in the computer centre. Printouts are softened. Soaps are hardened to wash away the skin and blood and leave the bones. The bones of man – hardened from the light, the bones that will live through the invisible years. These years spawned the centuries which we endure. They married the futures we begat. They sprang up in the past. They calculated the consequences of time. They accepted God's notes dated tomorrow. They paid in advance and laid watch on the machine tools and templates which made the negs and blueprints for heaven. They sealed the moment of true sentiment into the stars which cluster the quarks which are the mystery of time. These are the years when men to appear at all have to make their presence with music from spheres (infravide). With awareness of the solidity of space filling a void that no longer existed. These are the years when Joan of Arc submits to God and bears a son who is no Messiah. He is a wanderer allowed to lead where he wishes. He follows it to the cervix of the heart and leaves there a leaven which lights up the first again and brings them to this apocalypse, this ending, which is a beginning. Oh yes there are the bird years.

*although it wasn’t until 1984, ironically enough, that Paolozzi decorated Tottenham Court Road station with his mosaics which were replaced with the slickness of the Elizabeth line.

References:

https://realitystudio.org/bibliographic-bunker/my-own-mag/

http://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/little-british

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44341691

http://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28760/1/GOL_thesis_VowlesC_2006.pdf

https://www.frieze.com/article/jet-age-compendium-paolozzi-ambit

http://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/white-space-black-hat

I am glad to have met Martin Bax by walking round to his house and knocking on the door one morning, being politely accommodated even to being allowed to sit in the famous William Morris chair...

You write "The full archive can be found on Jstor, and a few libraries, including my own." Is yours online, and accessible? I would be so grateful if it is!

Marvellous piece. He was the centre of so many people and ideas